Image

by Bob Wood

Knowing my interest in things Pennsylvania Dutch, some time ago, a friend sent me an on-line catalogue detailing an auction at Sotheby’s, New York, of Pennsylvania Dutch antiques.

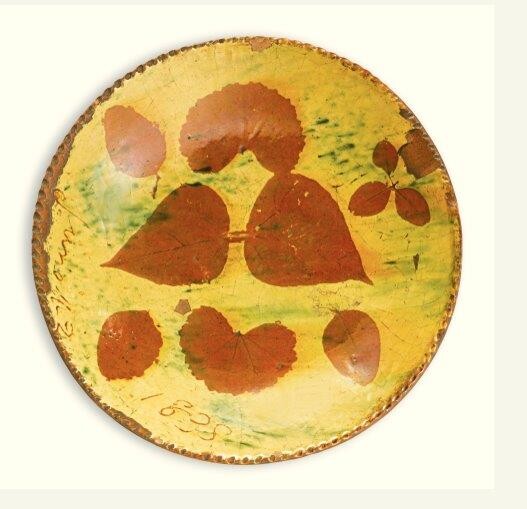

While scrolling through it, I was astonished to find two decorated dishes, dated 1838, made by Conrad Renninger in Montgomery County. I have an ancestor, Conrad Renninger who was the father of the potter also called Conrad. Conrad the potter was a brother to Charles Renninger from whom I descend. There were two plates: one a pie plate with leaf decoration and a larger one showing a horse. The leaf plate fetched $10,000, and the one with the horse was sold for $34,375.

Plate by Conrad Renninger, 1838: Esmerian Lot 509 Leaf Silhouette

Made in the thousands by most potters, pie dishes, “boi-schissel” in the dialect, are unlike any other local clay vessel. Rather small by today’s pie standards, the clay pie dish is rather low, curved and has neither rim nor base. The bottom is rounded, not flat, thus allowing the bake oven’s heat to penetrate evenly. What was baked was the fruit pie.

Fruits of all sorts, not as abundant in Europe, grew in profusion in Pennsylvania. Peaches, relatively unknown in Europe, here in Pennsylvania, were more or less free for the taking and often fed to the pigs. Tree fruits including cherries, pears, apples, plums, apricots, peaches, nectarines, quinces and even mulberries became pie filling, along with berries: gooseberries, currants, strawberries, raspberries, grapes, huckleberries, and wine berries. It should be noted that all of the tree fruits mentioned, and many of the berries, were not native to North America, but thrived in our soil and climate when brought here from around the world.

Said to be developed by the newly arrived English and Scotch Irish, the pastry shell fruit pie was quickly adopted by the Dutch. (“Dutch” in local writing always refers to Germans. The word “Dutch” being a corruption of the word for German—“Deitsch”). By some accounts, eaten at every meal, we would probably find the early pies rather skimpy, and tart. Said to be made without sugar, one early recipe called for only one-half inch of filling!

To make pie plates, the potter would take a double-fist size lump of clay and roll it out to the desired thickness with a wooden roller, much as the housewife would roll pie dough. Then, using a compass “disc-cutter,” he would cut the clay into round discs and let it dry for a bit. Since both he and his clients loved color and decoration, the potter would often add a bit of both to the discs with the “slip” cup. “Slip” was white New Jersey clay mixed with water to a creamy texture. The slip cup was tea cup size and had two or three hollow goose quills protruding from the bottom through which the liquid slip ran. With a few practiced movements, the potter embellished the disc with some wavy lines of decoration.

A broken pie plate mended with soft copper wire which allowed continued use. Photo courtesy of Goschenhoppen Historians.

When the slip was somewhat dried, it was pressed down into the clay disc to make a smooth surface so that the decoration did not protrude above the surrounding clay. (This step is often omitted by modern reproduction potters.) The flat disc was then pressed, decorated side down, onto a convex mold, there to get its permanent shape.

Just as the edge of a pie crust is trimmed, the potter cut the ragged edge of his semi-hard dish with a knife. Finally, using a small notched wheel called a coggle, affixed to a handle, the potter ran notches around the rim of the plate. This notched edge gave a pleasing finish to the dish while also strengthening it against chipping. A broken pie plate mended with soft copper wire which allowed continued

use.

Photo courtesy of Goschenhoppen Historians.

When the clay was quite dry the dish was quickly dipped into a glazing solution containing lead, which gave a smooth gloss to the plate when fired and turned the white slip a soft yellow. (An example of this pie plate can be found here.

Some potters, using both slip cups and free-hand application, made more elaborate decorations: flowers, birds and such. Another, and more rarely used, method is called “transfer decoration.” This is the method that Conrad Renninger used on the auctioned pieces.

One source describes the method thus: “A leaf from a maple or other tree was first allowed to wilt sufficiently to become quite limp. It was then moistened and made to adhere by pressing it firmly with the fingers on the unburned ware. An engobe [coating] of white slip was then spread over all and when dry the leaf was removed. An application of lead glaze then brought out the design clearly in a deep red color on a white or yellowish ground upon firing."

“The same process was occasionally employed for transferring pictures or figures which were cut out of paper, such as animals or other patterns. An example of this character is embellished with a silhouetted figure of a well-proportioned horse as the central design and a smaller at the side representing a double eagle and a heart….the pattern had been carefully cut out of stiff paper and laid on the surface of a coating of chocolate colored slip, and over all had been spread a layer of lighter colored clay, after which the paper design had been removed. This process, however, was not considered a professional one and was very rarely resorted to. The example described above bares on the back the name of the maker and date ‘Conrad K. Renninger, Montgomery County, June 23, 1838.’ ”

Photo courtesy of Goschenhoppen Historians.

Of Conrad, the potter, little is known. He was born in 1809 in New Hanover Township the son of Conrad and Susanna (Yoder) Renninger. He married Anna Nase in 1836. The only record of land owned by Conrad was in Frederick Township where he sold 32 acres in 1844 to John Shaner for $870.

Interestingly, later tax maps show a working pottery on John Shaner’s property on Hauck Road near Perkiomenville Road. Conrad apparently moved frequently and documents indicate he died in 1869 in Williamsport of palsy—no doubt the fate of many potters who worked with lead glazes.

[Bob Wood, writer, artist, potter, historian, presenter, and volunteer, has published four books and hundreds of columns on local history for local news media. He is a popular presenter at area historical societies and invites the public for wide-ranging discussions held at Studio B Fine Art Gallery throughout the year. Dates of his appearances are published in local media, on www.studiobbb.org or on Studio B Art Gallery’s Facebook page. January 2023 programs are listed below.]

Don't miss the opportunity to hear Bob Wood speak in person. The following programs will run thorough January, 2023, at Studio B Art Gallery, 39A E Philadelphia Ave, Boyertown, PA . Encore Presentations, newly revised.

January 8 (1:00- 2:00 pm): Some Interesting Stories About Very Early Schooling in Germanic Pennsylvania—Many early Germanic immigrants seemed to have “No great itch for learning,” so early schooling—such as it was--could be called spotty at best.

January 15 (1:00- 2:00 pm): Water Power on the Perkiomen and its Many Tributaries—A fresh look at the hundreds of various mills that dotted the banks of local streams, many mills running until well into the 20thcentury.

January 22 (1:00- 2:00 pm): A Fresh Look into the History, Legend, and Lore of Berks County’s Mountain Mary—Rather than fading with time, the story of Mountain Mary grows ever more complex.

January 29 (1:00- 2:00 pm): The Medieval Mind and the “Little Ice Age”—‘A Strange and Wondrous Succession of Changes in the Weather’— Into the Medieval mindset, seemingly exotic and bizarre to modern minds, came erratic and often bitterly cold weather.