Image

by Bob Wood

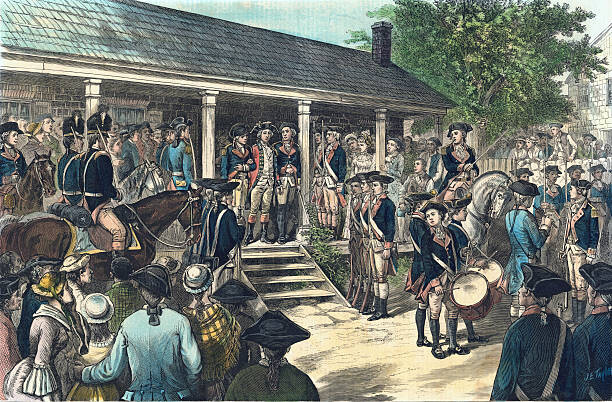

Other than George Washington, the most recognized name from the Revolutionary War is probably Benedict Arnold. That he was a “traitor” most people know, but what he did exactly is not so well known. A key player in the Benedict Arnold story was the officer in charge of British intelligence, Major John Andre (on-dray) briefly stayed at the Crooked Hill Tavern in Sanatoga—most recently Cutillo’s—where he was long remembered.

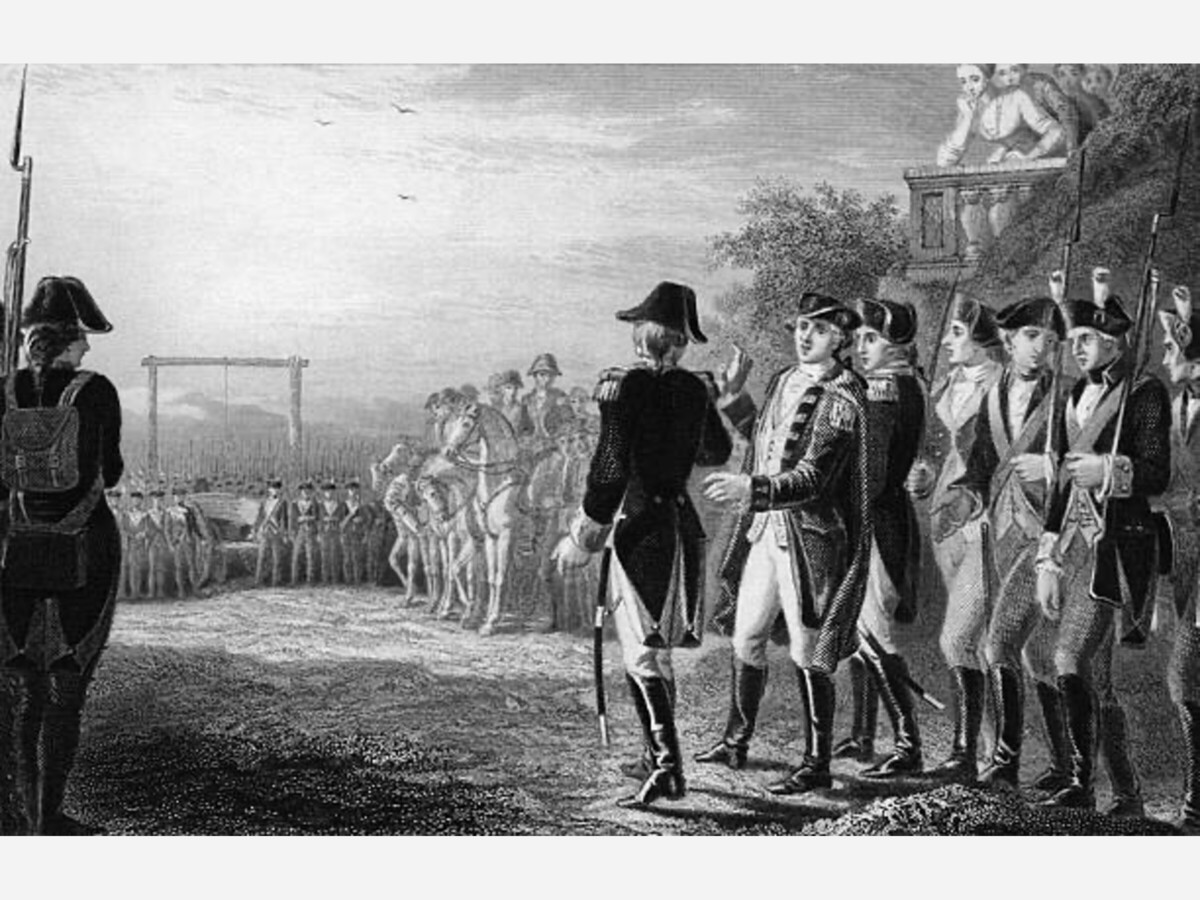

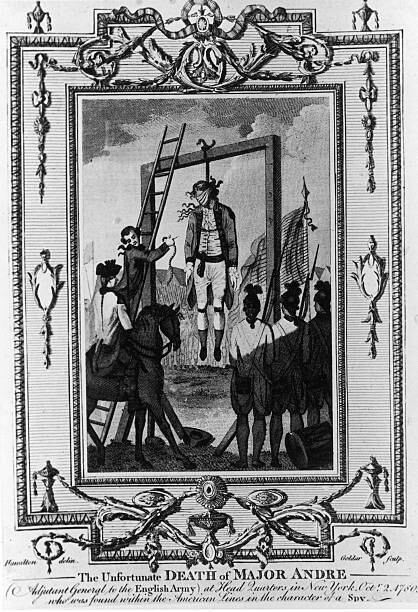

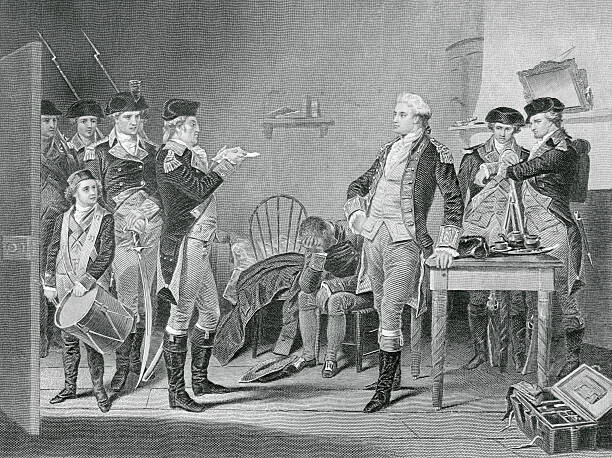

Major Andre was deeply involved with the Benedict Arnold treachery, and we can begin with his execution. After being caught by American militia and convicted of espionage by a board of inquiry made up of fourteen generals of General Washington’s staff, Andre was sentenced to hang.

General Washington communicated to General Clinton, then commander of British forces in America, that he would gladly return their Major Andre in exchange for the renegade American General Arnold who had absconded to British protection. The British said “no deal,” so on October 2, 1780, at Tappan, New York, Andre mounted the scaffold.

Andre’s American jailers wept as the gallant, charming, and well-liked officer said his last words, “I pray you to bear me witness that I met my fate like a brave man.” Andre’s execution offended the British probably more than any other event of the war.

How did Major Andre get himself into this fix? Andre was a thoroughly charming fellow well-liked by his comrades and loyalists. He was a handsome, polished gentleman. Talented in art and music he enjoyed theatricals and wrote some comic poetry.

Later writers have described Andre as “Mars’ butterfly” (Mars is the god of war). He enjoyed the good life, and was quite popular with the ladies. When the British occupied Philadelphia in the winter if 1777-‘78, Andre lived in Benjamin Franklin’s house and was romantically involved with Peggy Shippen, a popular Philadelphia socialite. After the British occupation, Peggy Shippen married the American General, Benedict Arnold, the officer then in charge of Philadelphia.

Some years later General Benedict Arnold was in command of West Point on the Hudson River. West Point was a critical American fortress that guarded the Hudson Valley. Its loss may well have doomed the American enterprise.

Benedict Arnold was a talented field commander and well liked by General Washington, but he was also ambitious and rendered himself obnoxious to other officers. While commanding Philadelphia after the British left, he was charged with various abuses of power which, it turns out, were true.

Arnold took offense to the subsequent troubles and charges. When he was later commander of West Point in 1780, he entered into secret negotiations with Major Andre, who was by then head of British intelligence, to arrange for the British capture of West Point for the sum of 20,000 pounds to be paid to Arnold if the plan succeeded and 10,000 if it didn’t.

The plan called for Sir Henry Clinton, commander of British forces in America, to attack the fort. However, Benedict Arnold’s defenses would be pre-planned and choreographed with the attacker’s so as to appear reasonable later on, but they would actually lead to the fall of the fort to the British.

To plan the details of the fort’s “capture,” Arnold and Andre wanted a meeting with Clinton. He agreed, but warned Andre not to go behind enemy lines, not to carry compromising papers, and to always remain in uniform. This would protect him from charges of spying if he were captured. Andre did none of the above.

On September 21, 1780, the British frigate H. M. S. Vulture delivered Andre to two loyalist farmers who rowed him ashore for his meeting. He met with Arnold accepting a sheaf of documents and spending the night at the home of his escort Joshua Smith.

Now fate played a hand (as she is wont to do). During the night the Vulture was being peppered by a shore battery, so it hoisted anchor and moved many miles down stream. Andre now had to travel overland through American held territory.

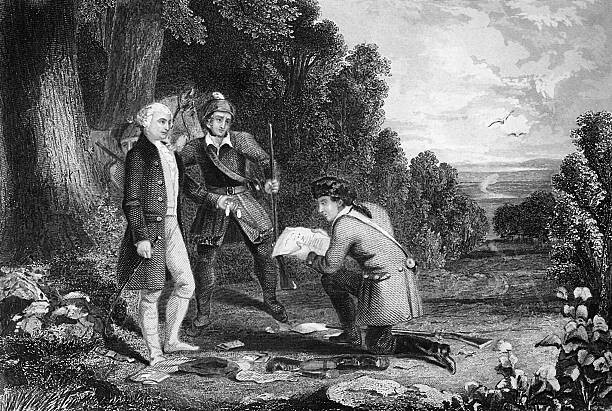

If he would have stayed in his officers’ uniform and carried a flag of truce, he could have passed through unmolested as this was commonly done. But, fond of theatricals and intrigue, Andre changed into civilian clothes and carried the papers in his boots. Smith accompanied him on all but the last fifteen miles, which were through British held territory.

Three men in British uniforms stopped Andre. He revealed his identity and ordered them to “give way.” However, the three were in fact American militia disguised as British soldiers. They searched Andre, found the papers and arrested him. At first it was thought he had stolen the papers, but an improbable sequence of events and near misses revealed that Benedict Arnold was the source of the documents. When the whole scheme unraveled, Arnold escaped to British lines.

One wonders what role Peggy Shippen may have played in all of this. She was, after all, Benedict Arnold’s wife and Andre’s old girlfriend from his Philadelphia days.

“The Gallant Major Andre” Part 2

There is a local legend that holds that Major John Andre, coconspirator in Benedict Arnold’s plot to turn over West Point to the British, had stayed at the Crooked Hill Tavern in Sanatoga for a week near the end of November in 1776. Cutillo’s is now located on this tavern site.

How Major Andre might have gotten here is as improbably as the rest of his story. He was captured by American forces on November 3, 1775, in Quebec. Shooting skirmishes of the Revolutionary War had actually started a full year before July 4, 1776. In the fall of 1775 American forces had attacked British positions in Canada where Andre along with other officers and soldiers were taken prisoner and subsequently held at Reading and inland at Lancaster.

At Lancaster the enlisted men were held in barracks, but officers were free to live at inns and private houses at their own expense. Andre was free to go where he pleased as long as he wore his British officer’s uniform and did not stray more than six miles from home. He lived with a loyalist Quaker family named Cope with whom he developed an abiding friendship.

Andre could speak fluent German, an advantage in that German-speaking region. He was an artist of no mean ability and entertained people with his flute. He began giving art lessons to the Cope’s eldest son. However, Lancaster was thought not secure enough and the prisoners were moved beyond the Susquehanna to Carlisle.

From Carlisle they were next sequestered at York and then set to return to New York for a prisoner exchange in the fall of 1776. While he was “captive,” he had a nice little shotgun for hunting, and, being forced to leave it behind, smashed it to pieces vowing, “No damned rebel will ever burn powder in it.”

Andre kept a meticulous journal with artistic renderings and maps of territories he passed through. However, the journals and maps of these early days are lost. No record exists of the officers’ route to New York or who escorted them.

The township history Lower Pottsgrove Crossroads of History says, “The story of Andre’s stay at Crooked Hill Tavern is challenged by the late historian Bill Claussen, who says the doomed officer never came closer to Crooked Hill than when the British were stationed near Valley Forge in September of 1777.

However, since nothing is known of the route by which the British prisoners were escorted, it’s not unreasonable to suggest that they might have come from York by way of the Lancaster Road now Route 30, then probably the most traveled road in the nation.

The officers and escorts would probably have come, at the officers’ expense, by stagecoach to Philadelphia and then up the Great Road, now Route 422, to Reading which was a major supply depot and base. Major Andre posted a letter to his old friends the Cope family in Lancaster from Reading on December 2, so we know he was in Reading on that date. This is all conjecture. There’s no solid proof that Andre stayed at the Crooked Hill Tavern, so the following story is best called a legend.

The story comes from fourteen-year-old Anna Maria Krause, born 1763 in Limerick Township near Crooked Hill. Her mother was from the influential Deering family of New Hanover and her Uncle Henry Deering was proprietor of the Crooked Hill tavern in 1776. Anna Maria often stayed and helped at her uncle’s tavern with her friend Kitty, Henry’s daughter. The following narrative is recorded in The Historical Society of Montgomery County’s Sketches, Vol. III, 1903. It is purported to be a verbatim account of one who knew Anna Maria which was recorded in a document titled The Wolff Memorial.

“Whilst [Anna Maria was] residing at the Crooked Hill, in December, 1776, a number of paroled British officers passed through, on their way to New York to be exchanged. The roads becoming impassable, they remained a week at her uncle’s [tavern] house.

Of the officers she retained vivid recollections, and often spoke of them in calling up reminiscences of her early life. Major Andre and Colonel North were of the party. Another, a young nobleman, was a mere stripling.

With Major Andre she seemed particularly impressed. He was then a prisoner for the first time, having been captured November 3, 1775 at St. John’s, at the head of Lake Champlain, and had been on parole about a year in Lancaster and Carlisle.

She had described him as rather under the average stature, of a light, agile frame, active in his movements, and of sprightly conversation. He was a fine performer on the flute, with which he beguiled the hours of twilight, and was an excellent vocalist.

Whilst in Mr. Deering’s house, Major Andre occupied most of his time in examining and drawing maps and charts of the country. She bore full testimony to his polished manners and the easy grace and charm of his conversation. His engaging deportment rendered him popular with his fellow-officers.”

The rest of the story is that the British command was much impressed by the fine maps of the territory through which Andre had sojourned.

His maps and journals of this early time are lost. In Winthrop Sargent’s Life of Major Andre reference is made to these lost journals in these words:

“Since he came to America, he had kept up a journal in which both pen and pencil were tasked to record his adventures and wanderings among Americans, Canadians, and savages. Everything of interest that he saw---bird, beast, or flower---was preserved by his brush in its native hue, and the volume exhibited not only views and plans of the regions he had traversed, but of the manners and apparel of their inhabitants.

“Even through captivity he had saved this precious memorial from the hands of this captors; and it may well be believed to have been of material service to him now. His memoir was well received; Sir William [Howe, General of British forces in America] was delighted with its ability and intelligence.”

His journals, drawings, and maps from 1777 to 1780 have been published in expensive folio editions.

Bob Wood--An inspiring Jack of all trades, master of many. Bob Wood serves as Studio B's Gallery Adjunct when he's not busy doing everything else! Writer, artist, potter, historian, and volunteer extraordinaire, Bob began his career as an artist following his retirement from teaching Language Arts. Bob invites the public for wide-ranging discussions on art, history, and the art and craft of writing. Bob has published four books on local history.