Image

by Bob Wood

Early tax records show that although the early farms (called “plantations” in the 18th century) often had only two or three cows, almost every farm had them. Milking and all that followed was the province of the farm wife and women. Women did the milking and the laborious process of butter making.

In the Colonial era, the twice-daily milking produced only about a gallon per cow. (With modern genetics, scientific feeding, and, hormone injections, some modern dairy farms can push a cow to produce ten times that amount.)

In 1800 the average cow produced about 80 pounds of butter per year; with careful breeding, this doubled by 1840. But 80 pounds of butter at 10 to fifteen cents per pound yielded a butter profit of roughly $10.00 per cow per year. There would have been an additional small profit from selling the calf for veal. However, this $20 butter profit from two cows would often balance the farmers’ accounts with the store and maybe leave a little extra money.

In “Pa. Agriculture and Country Life 1640-1840,” Fletcher notes: “The nondescript cattle of the colonists were valued chiefly for their meat and hides and as a source of motive power---milk was a by-product.”

Before the creamery era toward the end of the 19th century, the market for fluid milk was very limited at best. The milk of that time, delivered daily around town in buckets, turned rancid quickly as it was loaded with all sorts of bacteria and was often watered down to boot.

In general, people in those days were simply not milk users. Consequently, dairy profit around here was mainly from butter which could be retailed for fifteen to twenty cents a pound by the farmers and hucksters or bartered in trade at the village store for half that amount. The price was higher in the winter.

The process of turning milk into butter went something like this. The day’s milk would be put into a big cream-crock (rome-hoffa) and kept around sixty degrees in the spring house in the summer or the kitchen in the winter. After a day or two, the cream would float to the surface and be skimmed off with a large tin spoon (rome-leffel) that had many tiny holes. The fat globules would be held by the spoon while the skim-milk drained through the holes. The cream would be collected and kept cool in crocks until enough was accumulated for churning.

One day the mother would announce to the girls “Heidt wert ga-buttert. Fetch die butter-foss.” (Today we make butter. Get the churn). Generally, butter churns used around here were the barrel type that lay on their sides and had a shaft through the middle with a crank outside the barrel on one end.

Inside the barrel attached to the shaft were four paddles punctured with holes. The cream went in through a round opening about a foot wide midway of the barrel. This opening had tapered sides into which a lid fit tightly.

Perhaps in very early days they used the vertical kind of churn that had a plunger like “dasher” that was thrust up and down in the cream. Estate inventories around here, though, seem to list the “butter-foss”---“butter barrel” which indicates the barrel style churn.

First the churn was washed with soap and hot water, rinsed thoroughly and then scalded with boiling water. After the cream was poured in, the churning began. This was a tedious job and one often left to older children. What the churning accomplished was to break and rupture the globules or capsules of the cream so the long chains of butter fats would be released.

After about a half an hour, more or less depending on the temperature, the sound of the swishing of the churned changed and the mother would announce “New coomt er”--Now it’s coming. The crank became harder and harder to turn, and lo, the churn held butter. The fluid that remained was buttermilk which was poured off. If all the buttermilk wasn’t washed out, the butter became rancid. Some clear cold water was poured in and the crank turned for a few minutes to wash the butter which was scooped out of the churn by hand and placed in a large flat container where it could be additionally washed and then salted.

Since prices were higher in the winter, the thrifty farm wife would often thoroughly salt and store some of the summer’s crop in stone crocks in the cool spring house or cellar, then wash it off and market it in winter. But this was risky.

As Victor Diffenbach wrote in a 1952 issue of “The Pennsylvania Dutchman”: “If not enough salt had been used, or if it was kept too long to realize a few extra cents per pound, then a slump in the market requiring some more keeping [this] would finally result in a smelly, almost useless product. “Dar butter iss dronish,” the huckster would say to the farmer’s wife. “All I can sell it for is far back-butter (for baking butter).”

Most people are familiar with “butter molds.” Usually carved from hard, close-grained wood like maple or walnut, there are immense variations of wheat stalks or sheaves, tulips, six pointed stars and so on.

Most are round, but some are oblong or square. Most have a knob handle on the back, but some have a flat handle coming off the side. These were usually not pressed down on the butter to make a print; rather the butter maker held the mold upright in one hand and dropped a fist size hunk of butter down onto the mold which held the butter as she took a wooden paddle and added sides and smoothed it to the size she wanted.

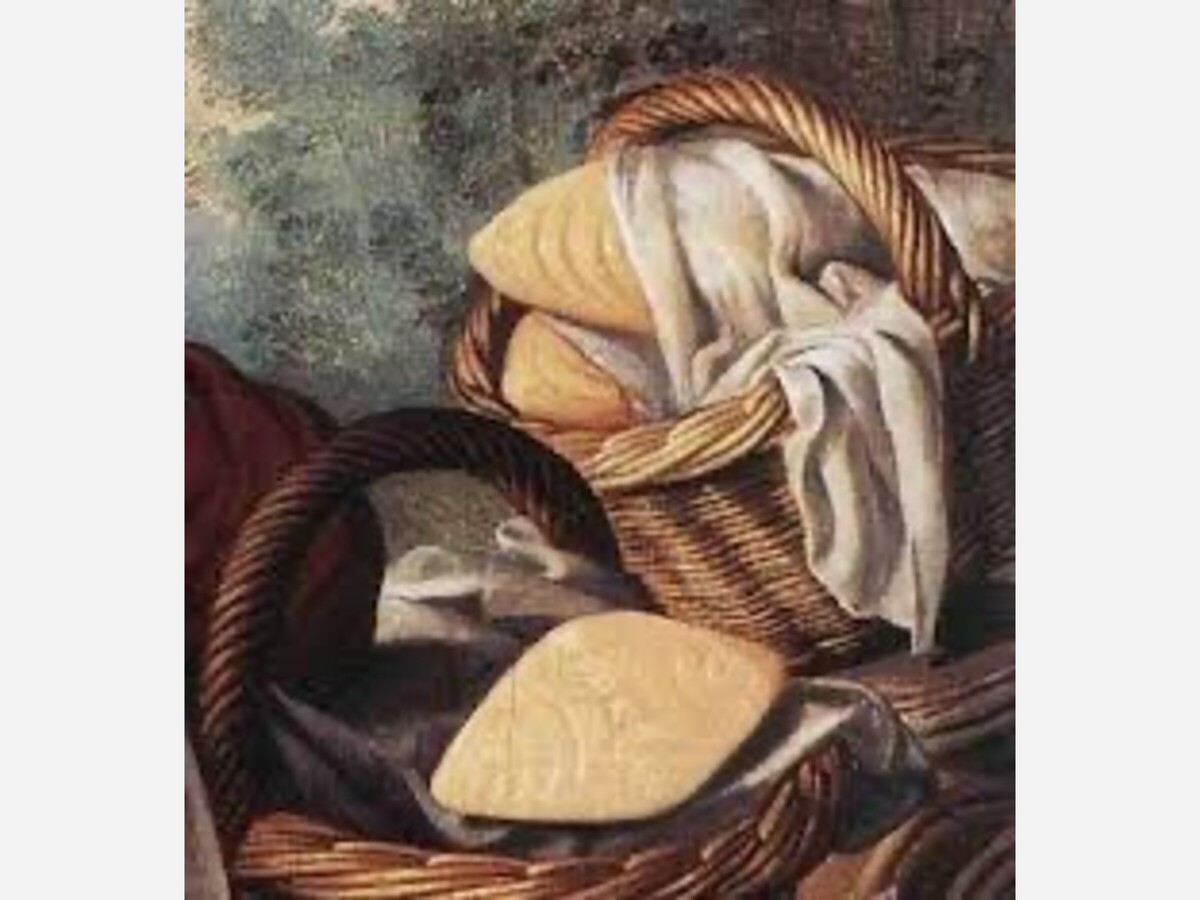

Then, if it was going to market, she placed it on a square of linen cloth and lifted the mold off, leaving the imprint facing up. The linen cloth wrapped around the butter kept it separate from the other butter pieces after it was put in the butter box for carrying to market.

The butter box was a rectangular wooden box that held about twenty pounds on separate shelves. If it was carried by horse, a bag of straw was placed between the box and the horse in warm weather so the horse’s heat didn’t melt the contents.

When someone bought a pound of butter, they brought a plate to put it on and the seller took the linen butter cloth home to be washed and reused.