Image

by Mike Strzelecki*

On any fair weather day you can see joggers plying the streets of Boyertown, training for local 5K runs, some reaching for a fall marathon. You probably won’t see Kyle Gery, however. Gery is one of Boyertown’s most talented and accomplished runners, but he operates in the shadows of the mainstream running community. He is an extreme athlete who prefers to run races of ungodly distances over obscenely difficult terrain, far from the well-trodden running routes. Gery is an ultrarunner.

Ultrarunners like Gery vibrate at a different frequency than road runners. They gravitate towards running races called ultras that are longer in distance than the traditional marathon. Ultra races typically range in distance from 50K (31 miles) to 100 miles, though some stretch much farther. Sometimes the races require days of continuous running, not just hours. Marathons are just warm-ups for these athletes.

Ultrarunners also seek out challenges beyond the distances. Ultras are often held in mountainous terrain, offering runners the additional obstacles of traversing rock-strewn trails, fording rivers, and clambering steep hillsides. The longer races extend into darkness, requiring runners to navigate trails using flashlights. The majority of ultras have strict cut-off times, often 30 hours for a 100-miler, and just finishing is often the goal.

Preparing for an ultra is much different than preparing for a road race. Instead of setting a pace and attempting to stick to that effort throughout the race, ultrarunners must learn to more efficiently manage their energy. They may opt to speed walk up hills instead of running them, or run harder in the cool evenings and back off during the heat of day. They may take sitting breaks or even naps in longer races. They must train their bodies to ingest copious calories while on the move, eating pizzas and hot dogs and burritos as they go. And staying on course in backcountry wilderness is a riddle unto itself.

Ultrarunners must also develop their mental stamina. This includes the ability to manage pain, the willingness to push your body onward when your quads are calling for a time-out (30 hours of continuous running can lose its novelty), and the capacity to deal with fears that pop up while running alone in the wilderness, often in the dark. (“Is that leaf rustling a bear? Is that twisted stick a rattlesnake?”) It is said that to complete a 100-mile race, you must train your mind to make finishing the race the most important thing in your life at that moment, or else you will talk yourself into dropping out.

Gery graduated from Boyertown High School in 1994 and is a commercial real estate investor, residing in Douglassville. He is calm and analytical, and has the slender build shared by many talented ultrarunners. Gery’s passion for outdoor challenges began at an early age, and extended through early adulthood when he dabbled in mountain biking and triathlons.

In 2012, Gery sought a next-level challenge. “I wanted to push my body harder,” he explains. “So I entered a 50-mile trail run in Virginia called Bull Run 50.” Bull Run 50 takes runners along the banks of the historic Occoquan Creek, passing through obscure Civil War battle sites where bullets and uniform buttons from the war can still be found. The race is known for its spring colors; runners move through fields of rich violet blue bells and get cheered on by stands of resplendent redbud and dogwood trees.

“After that race, I was hooked,” Gery says. “I wanted to run even farther. I found that I just loved running through the woods and enjoying nature.”

Gery quickly built up his running resume. He participated in a number of shorter, local ultras, and ventured north to Vermont to participate in a 100-mile race through the rough-and-tumble Green Mountains. In 2015, he decided to take a shot at the sport’s most iconic challenge: the Western States Endurance Run.

Western States is a larger-than-life 100-mile event run in late June, and traverses the Sierra Mountains of northern California. The race is known for its extremes: runners may stumble through 20 miles of snow and sub-freezing temperatures in the morning, and then descend through scorching tinderbox canyons in the afternoon, where temperatures can reach 100 degrees and shade is nowhere to be found. The trails on Western States are dusty and desolate, and the ubiquitous downhills are enough to jar fillings loose. Western States is the Boston Marathon of trail running, complete with media helicopters, masseurs, and 1,300 volunteers.

“I get that it seems like a crazy thing to do. But really, it's just training your mind to believe you CAN do things. It’s about developing the dedication and perseverance to accomplish goals - any goals - and tapping into the support of your family.” -- Andrew Styer

Gery came into the Western States 100 well trained. He handled the early miles with ease and felt strong heading into the canyons. But there is a saying in the ultra community: sometimes your mind writes checks that your body can’t cash. Gery’s body began waving the white flag. “My race did not go as planned,” he laments. “My kidneys shut down and forced me to drop at mile 48.”

Gery explains that your kidneys regulate electrolyte levels in your blood, which controls your heart rate and rhythm. “When my kidneys started to shut down, I was not sure what was happening to my body,” he says. “The extreme heat and exertion of the canyons put a lot of stress on my body. I started to cramp and my muscles were locking up. Then my heart rate was too high for my exertion and effort.”

Longer ultras such as Western States 100 often have medical personnel on site to handle such emergencies. A doctor examined Gery and recommended that he drop from the race. In ultrarunning parlance, Gery DNF’ed - Did Not Finish. Also in ultrarunning parlance, and more importantly, Gery DNF’ed - Did Nothing Fatal.

“When I fail at something, it makes it that much more important to find success,” Gery explains. “Western States 100 was my only DNF I ever had and it haunted me for seven years.”

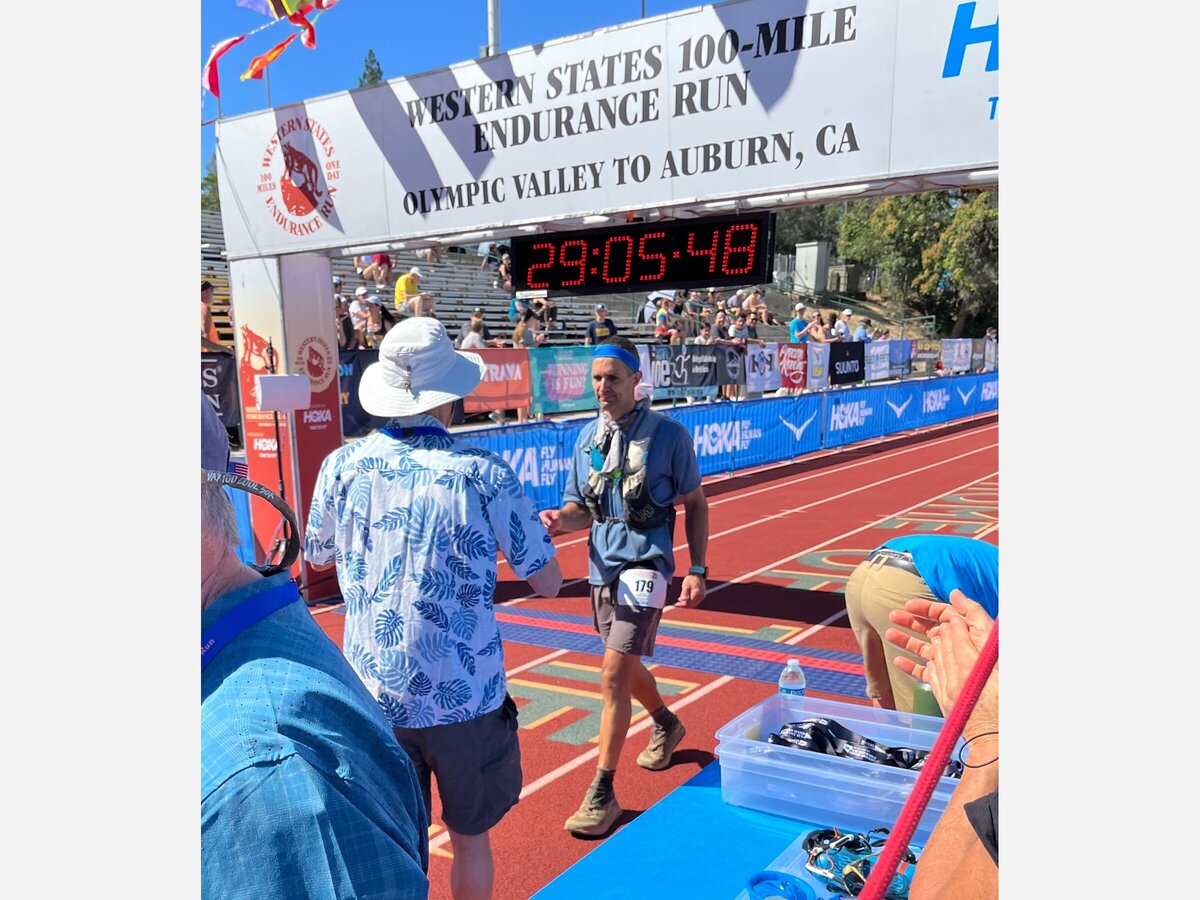

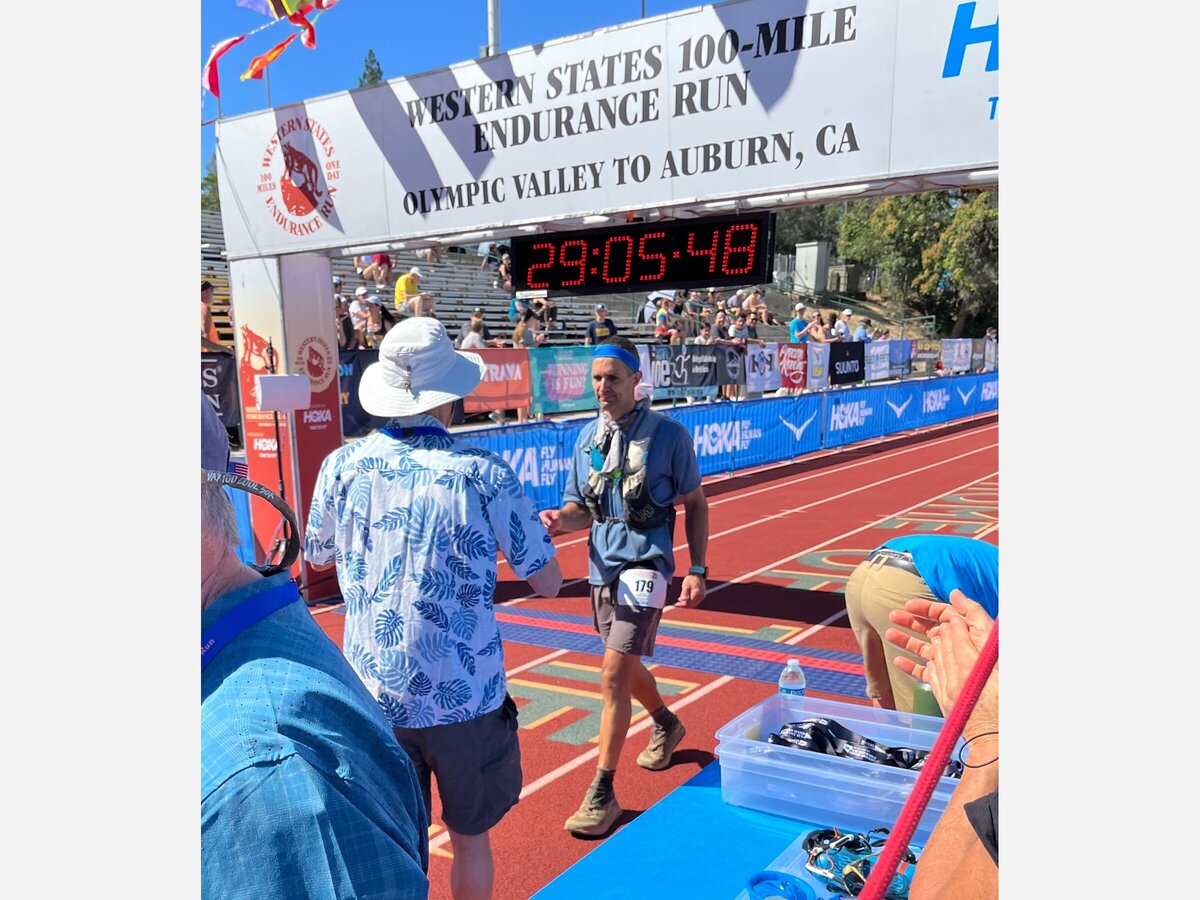

Gery was able to return for a second chance at Western States 100 this past summer, armed with the experience of having 25 more ultras under his belt, including other 100-milers. He ran strongly through the early uphills, over the snowy peaks, and felt decent heading into the prolonged downhills. But then he ran headlong into an old foe.

“At mile 30, coming out of the first canyon, I started losing kidney function again,” he sighs. “I was not able to urinate and was having trouble running.” Gery tried to reboot his kidneys by drinking ten cans of soda, but to no avail. As a more experienced runner this time around, Gery was able to adjust his race, slow his pace, and coax his body to the finish line.

Redemption is a powerful and personal experience. Gery crossed the finish line in 29 hours and 5 minutes, flanked by his wife and two children. He called it a memory he would cherish forever. His kidney function returned soon after.

“Running 100 miles might sound crazy to some people but it doesn't happen overnight,” says Gery. “It happens one small goal at a time. There is a lot of emotion involved when I set goals and crush them and I feel as if I am always a better person between the start and finish, facing all of the adversity in between.” Gery’s experience also exemplifies the notion that completing a 100-mile race is like solving a complicated puzzle; it takes patience, experience, problem-solving skills and often several iterations.

“I would challenge others to set goals that scare them a little bit and then go crush those goals and dream of things that are bigger than you think that you can handle,” he adds.

Gery chose running Western States 100, not only because it is the most iconic ultra in the country, but because it is also considered the first trail ultra - the race that started the sport. The origin of the 100-mile trail run can be traced to Gordy Ansleigh, a gritty woodsman-cum-chiropractor. Ansleigh regularly participated in a 100-mile endurance horse race in northern California known as the Tevis Cup. Just before the 1979 event, Ansleigh’s horse became lame. In what can be called either a stroke of genius or a lapse of common sense, Ansleigh covered the 100 miles on foot. He finished just shy of 24 hours, keeping pace with the equine competitors. The following year, he decided to ditch the horse and run the course again with a few friends. The Western States 100 footrace was born.

Some directors take perverse pleasure in designing races that make typical ultras seem mundane. The Hardrock Hundred Mile Endurance Run is a 48-hour scramble through the steep alpine precipices of Colorado’s San Juan Mountains. It features a lung-searing 66,000 vertical feet of climbing - like running up the Empire State Building 53 times. The Badwater Ultramarathon is a 135-mile run across California’s Death Valley, held at the hottest time of year - late July. Ambient temperatures often exceed 120 degrees and the road surface temperatures regularly creep above 200 degrees, melting running shoes.

The longest sanctioned ultra race in the world is the Self Transcendence 3,100 Mile Race. The course is a half-mile loop through a busy working-class neighborhood in Queens, New York. Participants must run that same loop 6,200 times, and have 52 days to do so. Essentially, finishers run almost three marathons a day, every day, for almost two consecutive months, around a short monotonous loop - all in the city summer heat. A handful of runners successfully tackle the course each year.

Ultras also have an element of danger, and can leave runners vulnerable. In a recent 100K race in China’s Gansu highlands, runners were moving through steamy backcountry terrain in shorts and singlets. An unexpected cold front swept through with rain, freezing temperatures, and wind gusts of 50 mph. Twenty-one of the 172 competitors perished from hypothermia and exposure. Running may be child’s play, but ultrarunning is not.

The majority of ultras, however, are safe, well-managed, and considered doable to the motivated runner. Almost 58,000 people in America completed an ultra in 2021 - a third of them women.

Mark Thompson making use of an aid station at mile 75 of the Yeti 100-Mile Endurance Run.

Mark Thompson making use of an aid station at mile 75 of the Yeti 100-Mile Endurance Run.Mark Thompson is another accomplished member of the local ultrarunning community. Thompson has spent the past two decades working in the pharmaceutical industry but spends much of his spare time on his Okie Dokie Farms in Colebrookdale Township. The farm features a menagerie of farm animals and Thompson hosts regular Yoga With Goats sessions. In what little spare time he has left, Thompson runs big miles.

Thompson’s path to running ultras began like so many others that come from the road running scene - by running a 5K as a challenge, and then a 10K as the next challenge, and so on. “I had a friend who was running 100-mile races,” says Thompson. “One day I just said. ‘That looks like fun, I think I want to run a 100-miler, too. And so I did.’”

Thompson jumped head-first onto the ultrarunning treadmill. He ran a 40-mile trail race around Blue Marsh Lake, in Reading, and lots of shorter trail races in the local mountains. In 2018, he tested his mettle at the Yeti 100 Mile Endurance Run in southern Virginia.

The Yeti 100 is run on a crushed gravel bike trail that follows the course of a former train that once carried lumber from the nearby mountains into the towns below. It is scenic with traverses of the lush Grayson Highlands mountains and sweeping valley views as the trail descends into the villages. Runners cross over 141 lovely railroad trestle bridges along the course.

Thompson learned that one of the challenges in running a 100-miles is merely staying awake for the entire race. “I was doing great through mile 50,” says Thompson. “But around miles 65 to 70, I started crashing. My feet were killing me and I was getting very tired.”

Thompson had a friend crewing his race - following along with him and providing aid and encouragement. “At aid stations, my crew filled my fluids and got me food,” he continues. “I was needing energy so my crew told me to grab some gummy worms to eat while I run. I grabbed a handful and began eating them. Apparently, I fell asleep while eating them standing up and started choking and coughing. My crew ran back to me to see what was wrong, and I suddenly woke up and coughed a mouthful of slimy, half-chewed sour gummy worms in his direction.”

The incident reawakened Thompson and he went on to finish the Yeti 100 in 28 hours and 40 minutes. He plans to return some day to try to break 24 hours. Running 100 miles in a day or less is considered a bragging point in the ultra community, and a worthy personal goal.

Thompson continues to run trail races of varying distances and degrees of difficulty. It remains the salve to his hectic life. “I like the solo time,” he remarks. “Normal life is always busy and there is so much to do. On trails, it’s just the miles and me. Nothing else. Sometimes I may run with a buddy which is good in a different way, but running solo is the best.”

Andrew Styer at the finish of the Laurel Highlands 70-Mile Ultra.

Andrew Styer at the finish of the Laurel Highlands 70-Mile Ultra.Andrew Styer also represents the Boyertown area on the ultrarunning circuit. Styer works in the electrical supply field and trains mostly on the rolling roads around his home in Pikeville. Like many local ultrarunners, he ventures out on weekends to Hamburg for longer runs on the Appalachian Trail. He is easily recognizable on the trails, often seen sporting a long, braided beard. Styer is a high-mileage runner, peaking out at 70 miles a week.

Styer prefers races in the 60- to 70-mile length, and gravitates towards those that offer challenging terrain. He has twice completed the Worlds End 100K trail race in the Endless Mountains of central Pennsylvania. Runners have 19 hours to scale 62 miles of steep, bouldery climbs, along the way crossing paths with splendid waterfalls and panoramic mountain views.

He has also finished the Laurel Highlands Ultramarathon - a 70-mile point-to-point traverse of the Laurel Highlands region of western Pennsylvania. Runners ascend 10 miles to a picturesque ridge, run 50 miles along the ridge past otherworldly ferns and rock formations, and then descend 10 miles to the finish. The technical nature of this race makes the effort similar to running a full 100 miles. Styer has completed over 25 ultras in all, and has his crosshairs on getting into the Western States 100 race soon.

Styer likes to philosophize the role extreme running has played in his development. “Ultras have given me challenges that have complemented my resiliency as a human being,” he notes. “When things get hard and I want to quit, being able to finish an ultra helps you to reframe what your mind thinks is possible.”

“They also have given me a tribe of friends I never knew existed prior to running ultras.”

Styer understands that his running experiences are not only unforgettable, but also unimaginable to others. “I've run away from black bears and have almost stepped on rattlesnakes,” he winces. “And I have also hallucinated that a tree in front of me was a trash can.” Ultras are uniquely suited to each runners' experiences.

Styer also recognizes, however, that the public perception of ultrarunners is a mixed bag - to much of the general public, ultrarunners operate on the fringe of sanity. “I get that it seems like a crazy thing to do,” he acknowledges. “But really, it's just training your mind to believe you CAN do things. It’s about developing the dedication and perseverance to accomplish goals - any goals - and tapping into the support of your family.”

[*Mike Strzelecki is a 1981 graduate of Boyertown High School and a freelance travel and outdoors writer. He writes from his home in Baltimore, Maryland.]