Image

[EDITOR'S NOTE: Love is in the air these days. Many have offered thoughts about this powerful emotion. This week, several of our readers share their thoughts in a series of guest essays.]

Love, of course, is one of the paramount human emotions, right up there with fear and anger. Fortunately, it’s capable of overcoming the latter two; but, for the average person, that’s a tall order. To love our neighbor as ourself (another application of the Golden Rule) is probably the only thing that will ultimately keep us from destroying each other through war, genocide, ecological degradation, and other expressions of fear, hatred, or greed. But that injunction doesn’t mean that we should feel as deep an emotional attachment to everyone else on Earth as we feel for our parents, our children, or our spouse. It means simply to recognize our common humanity with the rest of the human species and treat them with the same respect and kindness with which we would want them to treat us. The Commandment, after all, specifies that we should love our neighbor as we love ourselves.

But this suggests an unfortunate reason why doing so seems so difficult for so many people. Far too often and to far too great an extent, we don’t really love ourselves. Low self-esteem is endemic throughout Western civilization (except, perhaps, in certain halls of power where there appears to be an excess of egocentricity). Our manifest values—not the ones we claim to hold, but the ones we actually live out in our day-to-day lives—convince us that if we are not wealthy, attractive, talented, envied, and sought after, we are failures. Our highly competitive culture is characterized by celebrity worship, whether those celebrities are entertainers, athletes, business tycoons, super-models, or anything else that is likely to land them on magazine covers, television talk shows, and pop-culture websites. The power of electronic media magnifies the impact of any potential celebrity it thinks will draw the public’s attention, and it does so to the exclusion of virtually all others active in the same arena. The rest of us dwell in a perpetual state of obscurity and anonymity. Young people especially are deeply affected by this, sometimes to the point where they conclude that the only way they can get the world to acknowledge that they exist is to cram a weapon or two into their backpacks and open fire on their classmates at school.

But somewhere down deep we all have the desire for other people to be honest, kind, compassionate, and forgiving. This should tell us that if we can manage to be that way ourselves, we will not only secure the affection and respect of others; we will also find that we can look into a mirror and like what we see. Like what we see because we finally know who that person looking back at us really is: someone whose life is guided by the same foundational values that we all wish everyone else would hold. Someone who endeavors sincerely and consistently to treat others no differently from the way he would like to be treated himself. Someone who is worthy of not only respect, but emulation. And someone who is undeniably worthy of the affection and acceptance of others.

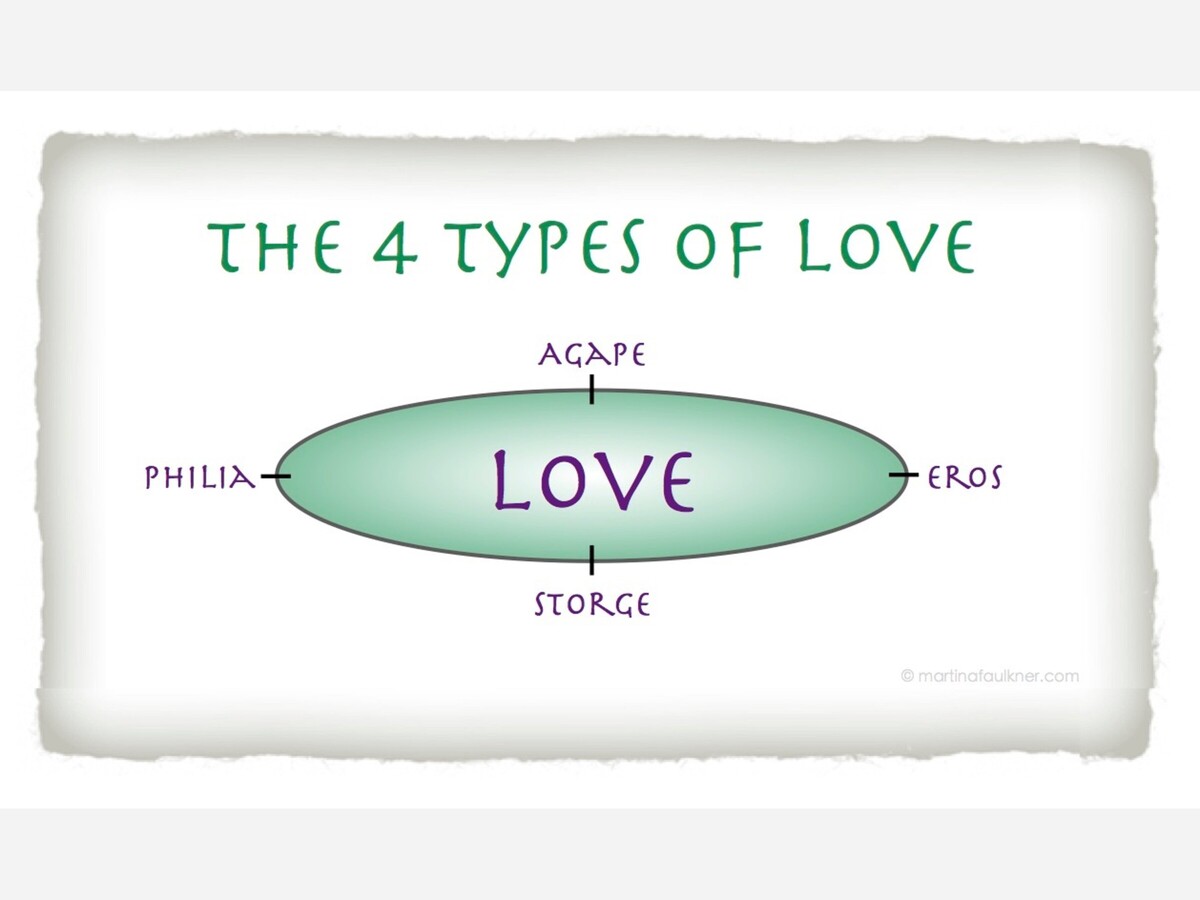

But the word love also brings to the minds of most of us the idea of romance, passionate attraction, and the ecstatic experiences that fall under the general heading of eros. Only a few generations ago, American culture was one of the most sexually repressive in the Western world. But things have changed. Nowadays, of course, sex is everywhere. But we in America have also learned, I suspect, that the sight of the unclothed human body will not suddenly turn observers into sexual psychopaths; that erotic desire is an entirely natural and universal aspect of the human organism and should not be regarded as a source of self-loathing and shame; and that with sex, as with anything else, the more familiar it becomes, the less fear it is likely to inspire. With these realizations, the erotic impulse may finally be freely accepted as what it has always been: the source of the most intimate, joyful, and mutually rewarding expression of one human being’s love for another of which we are capable.

The other kind of love—brotherly love, as it’s often referred to—is agape. Agape is what loving your neighbor as yourself is really all about. The Greeks gave us this dual understanding of love, recognizing that what you feel for your lover or your spouse is not quite what you feel for your friends or your neighbors. But these are two sides of the same coin. Agape is just another name for the recognition that we human beings, regardless of our skin color, our place of birth, our native language, or our way of relating to whatever it is that we mean by the word “God,” are all of the same family. If we trace the path of evolution back far enough, it becomes apparent that we all are descended from the same common ancestor. We all love our children, grieve for our deceased, fear the unknown, and possess the capacity to take great pleasure in music, story, and the beauty of the natural world that surrounds us. If we can bear this in mind whenever we encounter someone who is substantially different from ourselves, the world could become a much more peaceful, hospitable, and welcoming place.

* Craig H. Bennett, author of Nights on the Mountain and More Things in Heaven and Earth, available at amazon.com, barnesandnoble.com, and most book stores