Image

[ A 1981 graduate of Boyertown Area Senior High, Mike is a freelance travel and outdoors writer. He writes from his home in Baltimore, Maryland. If you missed his last equally fascinating article, "Off the Beaten Path: Boyertown 'Ultrarunners' Take It To the Limit," you can read it here. ]

When we heard that a volcano started erupting near the airport in Reykjavik, Iceland, three days before we were due to arrive, it caused concern that our trip would be canceled. After all, a volcano erupting in Iceland in 2010 shut down not only Reykjavik’s airport, but 300 others across Europe, for a week. The fine volcanic ash drifts freely across vast distances and wreaks havoc on precision jet engines.

We were thrilled to learn, however, that the eruption was not of the type that would threaten air travel. What we did not realize at that time is that this particular volcanic eruption would create one of the most indelible travel experiences of our lives.

The erupting volcano, known as the Fagradalsfjall volcano, is located in the Geldingadalir Valley of the Reykjanes Peninsula, in the Grindavikurbaer municipality, near the fishing village of Grindavik.

That is the most Icelandic sentence you will ever read.

Forget about the geographic specifics. Just picture this. You are standing on a coastal mountain on the south shore of Iceland, a thousand feet up, hugging the Arctic Circle. The mountain is raw and bare, virtually devoid of vegetation. Just volcanic rock of varying shades of grays and light browns, some covered with patches of gold lichen.

Now turn to the south. From high up, you are looking down at over ten miles of barren north Atlantic Ocean shoreline. Not a structure to be seen, not a tree anywhere. The only hint of man is a lonely road tracing the oceanfront’s path. If your timing is right, you may see a distant speck of a car pass. Hard volcanic rock is spilling down from the mountain, pushing out into the ocean swells. But the seas are punching back, with powerful bursting breakers battering the rocky shoreline. It is an eternal battle of territory between earth’s two greatest forces.

Now turn to the north. Waves of mountains off to the horizon - bare, wind-lashed, and unwelcoming. Some at odd angles to one another. You can look down into the valleys and see spreads of dark charcoal rock, the aftermath of recent eruptions - like massive ink stains across the landscape. Tiny spirals of smoke still rise from past eruption sites. In the distance, perhaps four miles away, from between two desolate mountains, rises a thicker wisp of smoke, white with a reddish hue, reaching high into the clouds. This is the erupting Fagradalsfjall volcano.

Since volcanic eruptions are rare and usually short-lived, our group decided to trek in to observe the volcano on our first full day in Iceland. Our group was my wife Kelly and our kids, and another family that shares our thirst for exploring. We decided to take advantage of this unique opportunity the Icelandic island gods handed to us. We researched and found that a safety area was established for observers, away from any poisonous gasses that may be emitted, but close enough to peer into the crater.

A 4:30am alarm put us at the trailhead at dawn. The hike to the volcano was 4.5 miles and included a few steep climbs and descents. The first mile was on a groomed pathway, part of the existing wilderness trail system. But after our first steep climb, the managed trail disappeared and the remainder of the hike involved off-trail scrambling across a lengthy and rocky ridgeline. The rocks ranged in size from footballs to ottomans, and were slanted at different angles. Hikers call these rocks ankle-breakers. On the first day of the eruption, three trekkers had to be helicoptered out with serious leg injuries.

The ridge trekking gave us insight into Iceland’s temperamental weather: we moved through a chilled cold - parka weather - and faced a couple hours of gusty winds and driving rain. Ominous, bunched-up clouds blocked any hope of sunlight.

There were no trail markers to follow. A series of short sticks driven into the ground marked the way to the observation area, but were hard to see in the storms. Generally, we moved in the direction of the eruption cloud, watching it get bigger as we got closer.

After two hours of wet rock-hopping, we descended a short hill, walked across a half-mile plateau, and caught our first glimpse of the erupting volcano. Witnessing such a dramatic eruption sends emotions scattering in many directions. There were audible gasps in our group, deep stares with a sense of disbelief, and weak knees. There may have been a few tears in response to the magnitude of what we were witnessing.

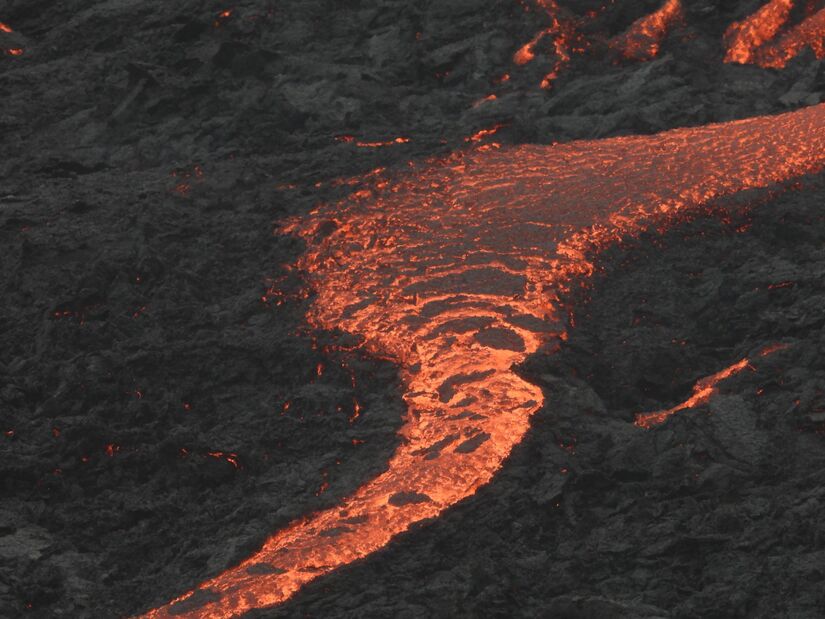

My first thought on seeing the eruption was our unique perspective of the display. How close we were able to get. We were perched on a table-top hill, gazing about 250 feet straight down into a barren valley the size of a small neighborhood. In the middle of the valley was a deep, circular gash in the earth surrounded by a shallow cone. Bright orange lava was spewing upwards from the cone in powerful, rhythmic pulses. Magma was spreading outwards from gaps in the cone, forming colorful braids across much of the small valley. The flow from the eruption ran to the base of the hill we were standing atop, where it began cooling to charcoal black.

The unusual color of the magma being cast skyward was arresting. It was a hue I have never seen in nature. Perhaps a fluorescent coral? A very light day-glo orange? Set against the earth tones of the surrounding hillsides, it was startling to see such vibrant colors spilling across the landscape.

Meditating on the eruption, it became clear what I was witnessing: the beating heart of our planet. It was like seeing the chest cavity of the earth ripped open and having a glimpse into its internal operations - what makes it run. It was a transporting experience, like stepping back into a different geological era.

The wind worked to our favor, blowing possible dangerous emissions away from our viewing area. Still clad in winter apparel, an occasional wind-shift would briefly send the heat our way; it felt like stepping out of an air-conditioned room into sticky summer swelter.

We watched the volcano erupt for about two hours. We gasped when the interior walls of the cone caved back into the crater and instantly melted to liquid rock before our eyes. We watched the expressions of other trekkers seeing the spectacle for the first time. We marveled at the ever-changing patterns of the magma flowing across the landscape. It was difficult to pull ourselves away.

My family has witnessed two past volcanic eruptions. In 2009, we traveled to Costa Rica to see the eruption of Arenal, a large coned volcano in lush, remote rainforest. We spent four days at an observation station on an adjoining mountain, watching rocks the size of small cars spit from the top and bounce down the barren cone face with great thunder. Each bounding rock sounded like a Blue Angels flyover, and intermittent round-the-clock eruptions kept us up at night. In 2015, we happened to be in Hawaii during the Kilauea volcano eruption in Volcanoes National Park, but it amounted to little more than seeing a red glow emanate from a low-lying crater at night.

But the Fagradalsfjall volcano was what one hopes to see when viewing an erupting volcano. Bright colors, dramatic eruption patterns, a unique vantage point - all set in an otherworldly landscape that looks more like the surface of Mars than an earthly continent.

Why is Iceland such a hotbed for volcanic activity? It’s because the island lies atop the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, the linear boundary where two great tectonic plates meet - the North American plate and the Eurasion plate. The plates are moving apart at about an inch a year, and as they do, molten rock from deep within the earth rises to fill that void. Sometimes the molten rock finds a path to the earth’s surface, creating an eruption. Volcanic eruptions are often forewarned; this one was signaled by over 10,000 earthquakes in the area in the three days leading up to the initial eruption.

Volcanoes in mythology and lore have often been designated as symbols of death. After seeing one so intimately, I prefer to see them as representations of life. They are vessels for change, constantly reforming the geomorphology of the landscape, persistently splashing new colors on the mountainsides and in the valleys. Iceland is an island forged by volcanic activity and, as such, will never remain static. It will never be the same place two days in a row. Volcanoes bring places like Iceland to life.

The remainder of our Icelandic journey involved seeing other spectacular natural wonders. We climbed deep into a narrow rift where the two tectonic plates are pulling apart. We witnessed waterfalls that made Niagara Falls appear pedestrian, and trekked through remote canyons that left us feeling like the only people on earth. We ferried to an island to watch hundreds of puffins devour fish, prepping for their annual fall migration.

But when we boarded our Icelandair flight back to the United States, and the captain told us we were free to move about the cabin, I rested my head back to catch some needed rest. And the vision that persistently reappeared in my mind was not that of waterfalls or remote canyons or puffin rookeries. It was of the erupting volcano blazing and dancing across that desolate valley. The same image that will stick with me forever.

The view from the base of the hill that Mike Strzelecki and his family were standing atop. Magma was spreading outwards, forming colorful braids across much of the small valley.

The view from the base of the hill that Mike Strzelecki and his family were standing atop. Magma was spreading outwards, forming colorful braids across much of the small valley.