Image

by Craig Bennett*

ON BECOMING HUMAN

By this point in my life, I should certainly have a fairly solid idea of what it means to be human. I’d like to believe that I do, but I have to acknowledge that I’m still learning. Perhaps that’s one of the more important aspects of being human: no matter how much we may think we know or understand, there’s always room to acquire more knowledge, develop greater understanding.

I was fortunate to have a couple of excellent role models close at hand when I was growing up: my parents. But parents and family members are so familiar, so much a part of our daily environment while we’re young, that it’s difficult to be aware of what we’re learning, day-by-day and hour-by-hour, from their example. Consequently, I didn’t really recognize a great many lessons in being human until I began to encounter them elsewhere.

For me, that elsewhere was chiefly in books. I had always enjoyed books, but I didn’t become a really serious reader until I started college. As an English major, I was required to read a ton of literature that I most likely would never have been exposed to otherwise. And I learned about a lot more that I made it my business to read during the summer months when I had no classes.

This is where I was introduced to some of the finest people I’ve ever met. It’s where I learned about the circumstances and events of their lives that became the first deep and meaningful lessons in how to be a human being that I actually recognized as such. The novels that I read during the summer—including those originally written in various foreign languages, translations of which were simply not the substance of courses offered at my small liberal arts college—became, along with much of the poetry and drama that I read for academic credit, a moral education the like of which would have been impossible to gain in another dozen lifetimes without them.

Oddly enough, one of the first such works I read offered me the example that has remained my favorite and most influential ever since: Alexei Karamazov. Alyosha, as he is known in the novel, is a novice monk and the youngest of three brothers. He and his brothers represent the three aspects of us human beings: the intellectual (Ivan), the sensual (Dmitri), and the spiritual, Alyosha himself. And spiritual he is: innocent, entirely non-judgmental, and concerned far more for the welfare of others than for himself.

The novel is long and full of many episodes; but the one that will always remain with me is his speech at the stone, the burial place of little Ilyusha, whom the group of boys to whom he spoke had been teasing and insulting when he first became involved with them. The story of how he turned them from being Ilyusha’s tormentors into being his friends and protectors is deeply moving—and deeply insightful. And Alyosha’s conduct toward all the many characters in the entire lengthy novel should excite nothing but the reader’s admiration and the wish to be more like him.

And who can read To Kill a Mocking Bird without being deeply impressed by the courage, wisdom, and goodness of Atticus Finch, the father everyone wishes he or she could have had?

Who can read Anna Karenina without coming away with a deeper understanding of women who are trapped in a deeply unsatisfying marriage and a greater sympathy for whatever transgressions they may commit in a desperate attempt to escape, if only temporarily, its emotional vacuum and dreariness? And who can come away, also, without a deep respect and gratitude for people like Konstantin Levin, the quiet, modest lover who marries one of Anna’s close friends and provides the reader a model of what Anna had hoped her own marriage would be?

Who can read Les Miserables without wishing that the world were populated more heavily with people like Jean Valjean; or Return of the Native without being moved by the patient, steadfast, and selfless love that Diggory Venn held for Thomasin Yeobright; or Far from the Madding Crowd without being impressed by the unwavering, understanding, and forgiving love that Gabriel Oak felt for Bathsheba Everdene?

Who can read Zorba the Greek without realizing that people with a formidable array of minor faults and human weaknesses can also be among the kindest, most compassionate, and wisest people they will ever meet?

As a certified, duly registered, card-carrying introvert, I’ve generally preferred activities that I can do by myself rather than those that are done in pairs or groups. But I’m not entirely certain that reading, for me, qualifies as a solitary activity. After all, it’s exactly where I’ve met many of the most admirable and interesting people I’ve ever known.

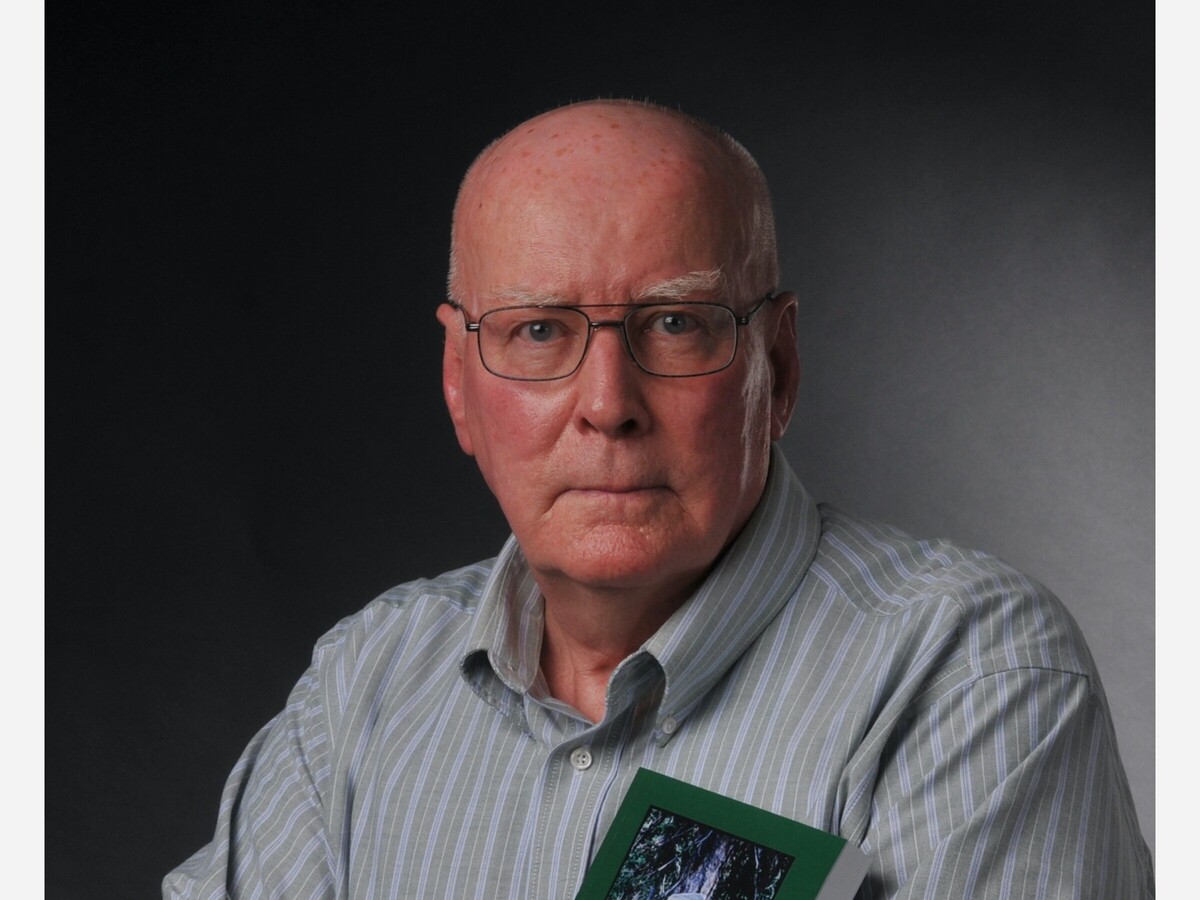

* Craig H. Bennett holds degrees from Ursinus College and The Johns Hopkins University and is retired from the two-year college faculty of Valley Forge Military Academy and College. Prior to that he taught English in the Boyertown Area School District. He is the author of Nights on the Mountain and More Things in Heaven and Earth.

Thanks, Craig. The school where I taught for many years had part of the curriculum touching on this very topic--being human, and you demonstrated here how that happens--being open to all everything around us (including reading and all that raises our consciousness (and conscience to a finer, "higher" level of awarenss of the world outside us and inside us. Thanks agin for the contributions to Expression