Image

Editor's Note: Studio B Art Gallery bids artist Joe Szimhart a fond farewell as he embarks on yet another life adventure--a return to New Mexico where he spent his earlier artistic life and where his wife longs to return. Joe has been a loyal member and participant in Studio B's exhibits and projects and created St. Columbkill's Bear Fever bear--"Papa Dickon." Happy Trails, Joe....As he reminded us, "Hello is just a text away."

by Jane Stahl

Finding a white arrowhead while digging up rocks in the Manatawny Creek when he was just a boy was a magical moment for award-winning artist Joe Szimhart, triggering questions about connections to the past, the people who hunted there, and what they were hunting, for example, at this spot which, in Lenape, was named “where we come to drink.”

Joe has spent a lifetime exploring the meaning of existence. His journey took him from studying engineering in college to majoring in a long-held interest in art, to living in the Southwest for 18 years as part of a religious cult, and returning to his roots—“God soaked” from exploring all manner of religions and belief systems, most recently offering assistance to families as a deprogrammer of those who had, like himself, found themselves in trouble asking what became a really bad question for them: “What do you think is true?”

Joe is still exploring the meaning of the universe but long ago abandoned the “toys, bells and whistles” offered by psychedelic experiences, ceremonies, Native American sweats, fasts, or mystical quests found in cultures as old as man. “Every culture has its myths, traditions and tokens—snakes, lions, for example, and symbols for the Creator,” he explains.

Joe has explored a lot of material on comparative religions, human behavior, even magic designed to fool us, in order to delineate the difference between healthy and unhealthy attachments and beliefs. His artwork reflects the journey. He has studied religions that became major ones; other bizarre belief systems that revolved around a charismatic figure—some that eventually vanished; some that were dangerous.

He recalls a song that begins, “When I was a cave man painting on a wall, I never had a dollar, man, I had it all.” The lyrics continue in the second verse with “I can fly” and recount a point when humans seem to become different where life becomes complicated—the point when we gather, acquire, and follow ambitions, develop math and technology.

“Are we doing anything today different than writing on a wall?” he asks rhetorically. In answering, he says, “Not really. We continue to come back to what makes us human. We go back to our origins—the Golden Age or whatever we call it. The difference is that we have become more destructive,” he adds.

Today he’s grounded in the cognitive “here and now,” making the best of the experiences offered by the spiritual elements that religious practices afford him. “Today I realize that the spiritual practices themselves are not the end game. I can go into any culture’s ‘dream time’ and understand the meaning and feeling of the Lord’s Prayer in a religious moment—perhaps better than any fellow Catholic churchgoer. I just don’t stay there; I make the best of the moment in a practical way and let it go. I don’t get stuck. And then, like anyone, I still get anxious, worry, can’t sleep, still have questions about what I’m doing in ‘real time.’”

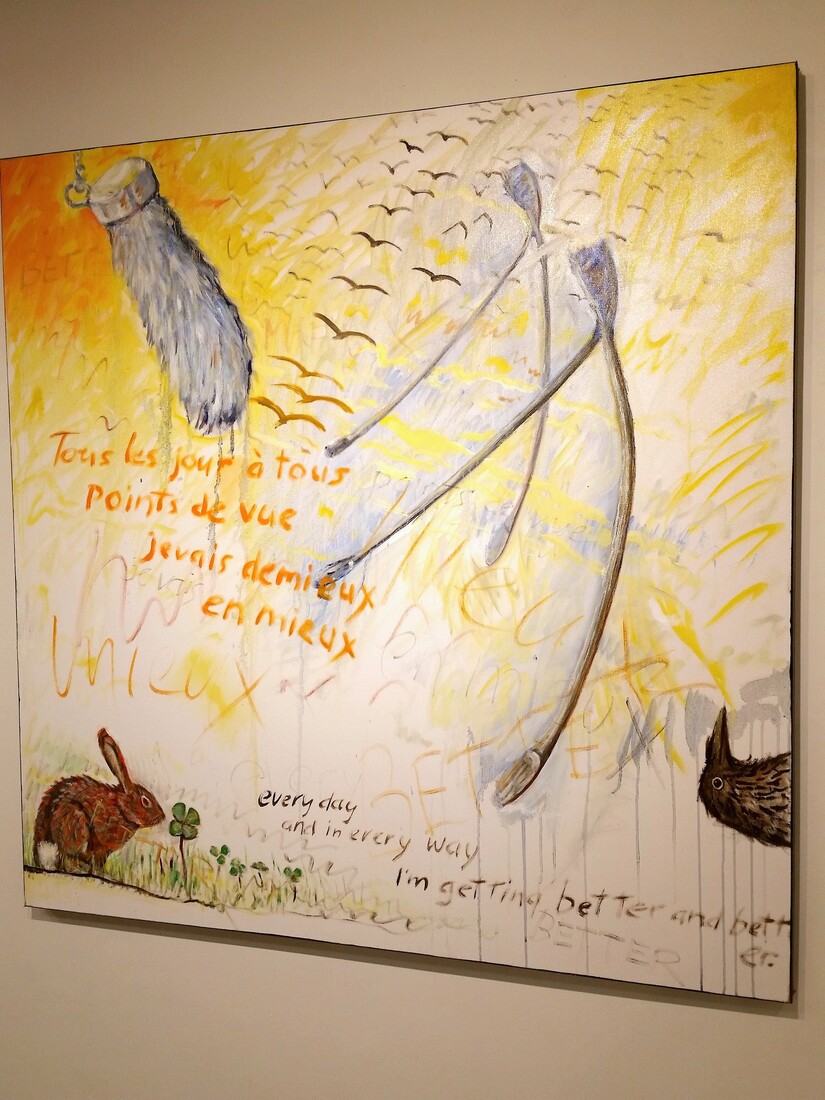

Joe’s current artwork continues his quest to connect with the past and make meaning. A current series of seven paintings resembles neolithic cave drawings or pictographs, often adding words. “It’s like writing on a wall; I graffiti my own work!” he offers. One piece “Dingo Dreaming” features an Australian animal surrounded by other elements common to the Australian culture.

“I have family connections in Australia and recognize the unique spirituality of the Australian culture,” Joe suggests. “There is a belief about time—there’s no before or after; time is on-going, ever-present, never stopping. To be involved, an aboriginal would need to fast, participate in a mystical quest, meditate on stories of the past, creator, snake, whatever the culture says to get to dream time. In my painting, the dingo is in dream time; the images surrounding him represent what he may be dreaming. I enjoy the images, playing with a lot of stuff. Nothing is resolved in the painting, but for me it was complete enough. Part of it is just having fun.

“A lot of time what I’m pushing for is merely something that pleases me. I sometimes start with an idea, follow where the piece takes me. It’s a conversation with the medium, the unintended consequences of creativity. And when it pleases me, I’ll varnish it and call it a day.”

In other paintings, Joe focuses on Native American culture. A birchbark canoe is centered in one painting inspired by a video that detailed what has become a lost art for Native Americans.

"It's an extraordinary video showing how to build a birchbark canoe that is to be a wedding gift. As it happens, the couple comes to help with the building. The details involved in the building of it--choosing the right kind of roots, the right kind of pitch and gum from the tree, the mix of ash and carbon to waterproof the seams--show the wisdom and skill of the Native Americans. They cut wood with old tools that would have been used back then-- to create over 100 ribs. It was an intricate process and took a long time," he explains.

"Native Americans developed this elegant canoe without technology or modern math. My painting is a celebration of the birchbark canoe and the culture that allowed its creation. The painting resembles a painting on a wall, not a scene but includes images that would have been important to Native Americans: fish, eel, a shield," he concludes.

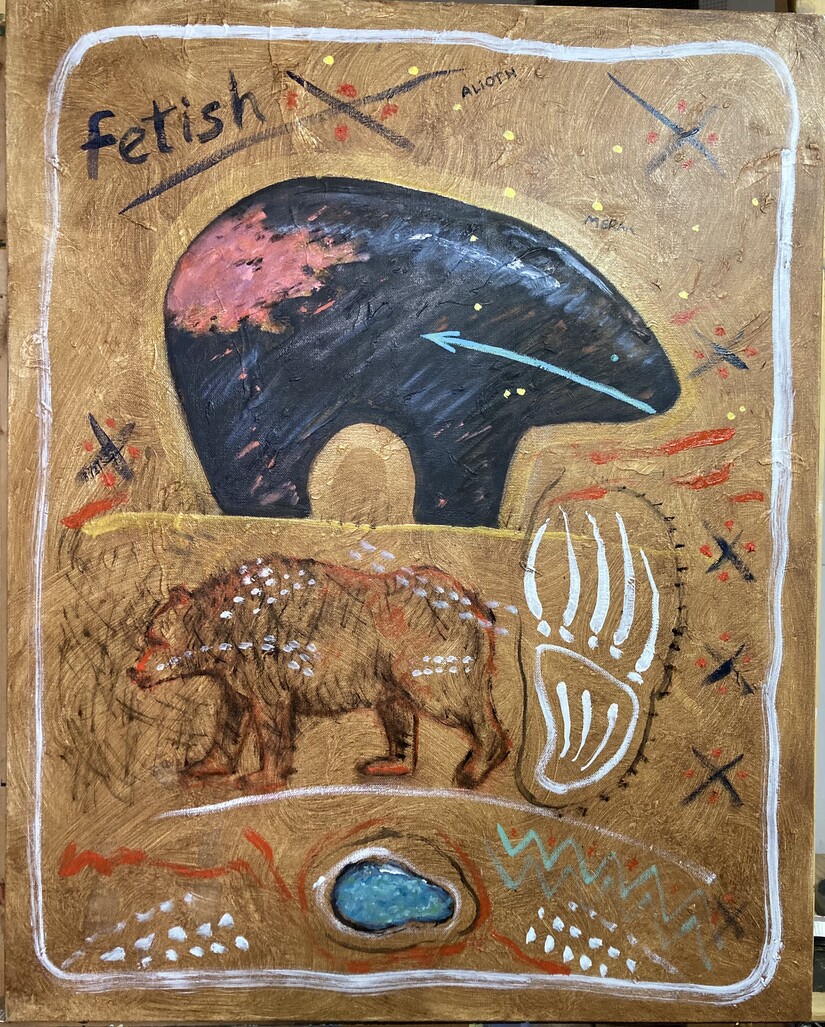

A fetish bear is featured in another painting. “Often in stylized bear paintings, the Native Americans had a heartline, maybe an arrow from the mouth of the bear to the heart, symbolizing taking in energy from the world to the heart,” he explains. “Native Americans valued tokens of bears or lions, sometimes wrapped in leather with a feather or bead attached. representing the spirit of the animal and becoming sacred objects.”

Joe describes a commentary he read suggesting that early man did art as mental survival; expression—art—was a survival tool, that there’s a switch in the human brain that created a sense of judgment about reality that animals don’t have. “Animals rely on instinct; man has the ability to reflect on reality, an ability that led to philosophy, religion, artistic expression, aesthetics. This ability has existed in primitive form and continues today in order to reflect the finer aspects of ourselves.

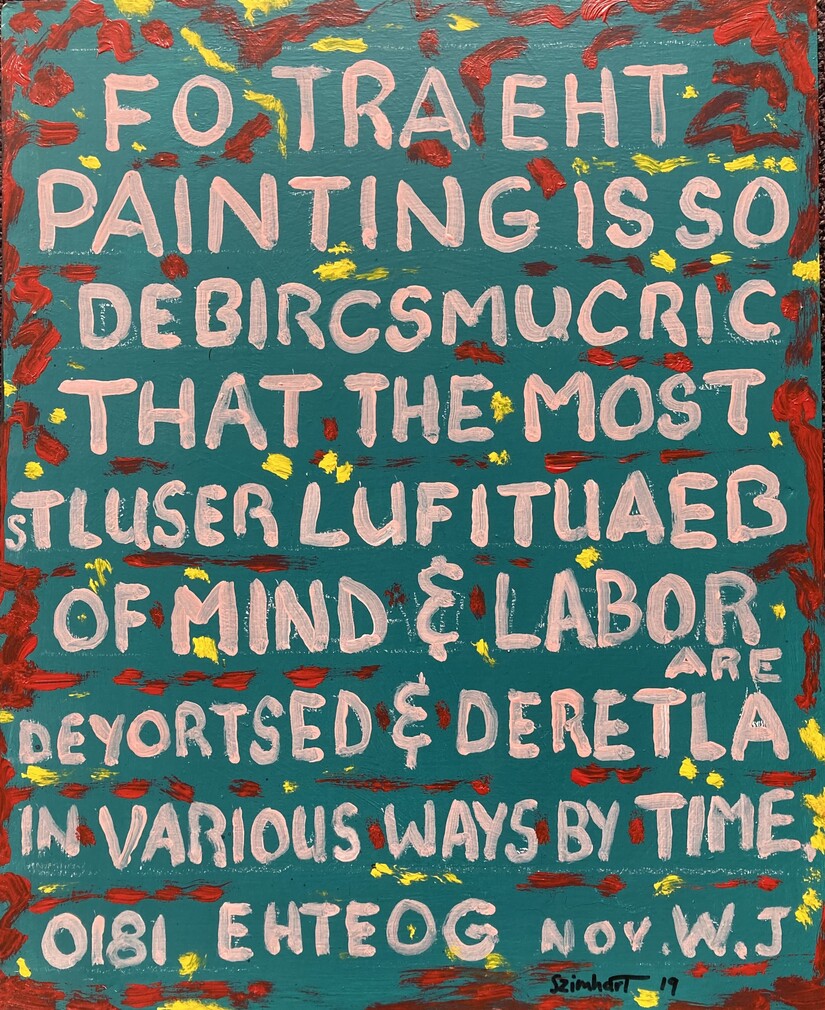

“Language becomes our vehicle for sociability and the development of psychology, sociology, psycho- and neurological sciences,” he continues. Fittingly, in a series of almost 30 paintings of all words, Joe plays with the brain in writing messages in an ancient Etruscan way of writing known as “plowing” in which the first line reading left to right; the second right to left, and so on. The work is a challenge to everyone’s way of reading a painting. The intention is to turn things around—out of time, out of mind, flip the routine, play with people’s brains, create new synapses. “The brain gets used to it,” he quips.

From the white arrowhead in Manatawny Creek to New Mexico to the culture of the Native American, Joe’s journey brought him back to Pennsylvania to care for his 99-year-old mother.

“My wife would return to the Southwest today,” he shares. [Getting her wish, she and Joe leave the area within the week.] For now, we can experience her “heartland” through Joe’s paintings—the stark colors of the desert—a gray tan, silvery green—a particular kind of beauty—and the brilliant colors of an Australian sunset and the flowers following a storm.

The conversation with Joe from which this article was created can be found on the "B Inspired" podcast, available on your favorite podcast platform including Anchor FM, Spotify, Google, Castbox, Breaker, Overcast, Pocket Casts, and RadioPublic, and Apple.