Image

by Mike Strzelecki *

The difference between “Bird Watching” and “Birding” is defined by the level of commitment to the task. Bird watchers enjoy observing birds flit about in their backyards or local parks, and often attempt to identify the birds they see. Birders take the activity to another level. They drive (or fly) long distances to observe a wider variety of birds. They often keep life lists and jot down observations. And they take a deeper - and often more science-oriented - interest in bird behavior.

It was with much appreciation and joy that my wife Kelly and I recently had the opportunity to spend a morning with a group of fervent ornithologist birders, capturing and banding a wide variety of bird species to better learn their behaviors and movements.

We convened at the Masonville Cove nature center, in south Baltimore. The nature center and grounds span 54 acres of marshland and reedy fields that were once industrial, but have since become overgrown and weedy and abandoned - perfect bird habitat. We could see the Baltimore skyline directly across the Middle River from our perch, a rackety quarry operations to our left, and an enormous parking lot to our right holding about 10,000 shiny new Mercedes Benz cars that were recently shipped to Baltimore and were awaiting distribution to dealerships. We were a stone’s throw from a pair of active bald eagle nests.

The bird banding was conducted by a group called Birds of Urban Baltimore in conjunction with other non-profit groups and federal agencies. About ten people were actively involved in the banding operation and there were a handful of observers. Our intention on this day was to learn the process of bird banding and decide whether we want to navigate the extensive training required to be part of the actual banding. (Spoiler alert: It became apparent pretty quickly that my puffy sausage fingers would never be able to safely grasp and manipulate a bird that weighs one-fifth of an ounce.)

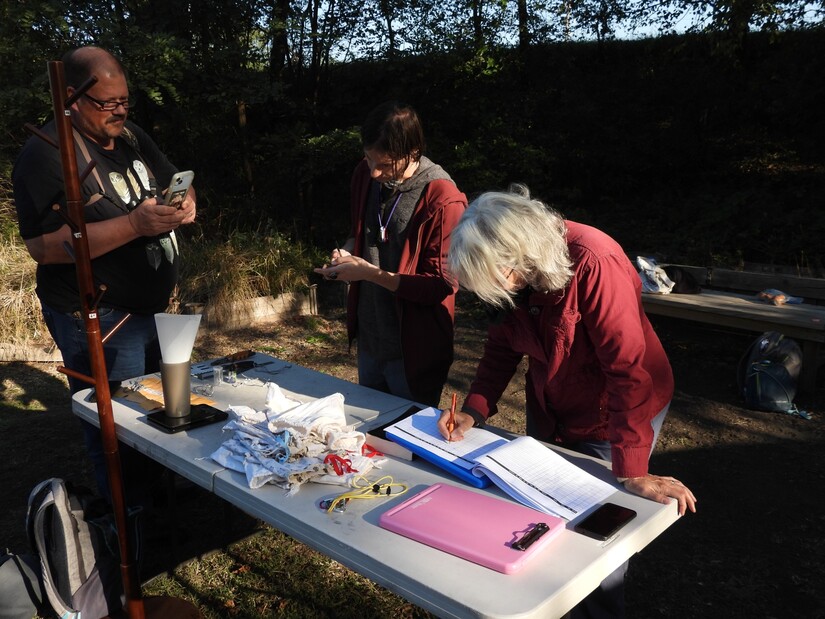

Birds were captured in thin, gossamer-like material strung between two poles that resembled low-slung volleyball nets. This operation had six nets spread across various weedy meadows. Nets were checked every half hour. Captured birds would be carefully unraveled from the nets and placed in small cotton sacks to help calm them. They were then transported to a central research table, where the science began.

The banding crew first identified each bird by species and then attempted to determine the gender of each by observing field marks like colorations and wing patterns. They then estimated the bird’s age by looking at the wing and tail feathers. Much like trees can be aged by counting growth rings, birds can be aged by observing growth patterns in feathers. In times of abundant food, feather growth exhibits a different color than times of sparse food, which tend to be seasonal variations. As such, the wing feathers and tail feathers of birds often exhibit their own form of growth rings.

The researchers then tried to estimate the amount of fat on a bird. It takes exceptional expertise to assess the fat content of a creature that weighs only a few grams. They did so by blowing on the bird’s fine stomach feathers to open up the belly area, and then quickly and roughly guessing how much fat they observed. The amount of fat estimated gives indication to where the bird is in its migration and how long it has been feeding at this particular location.

The banding of the bird was next, and requires a special level of nimbleness and finger agility that few possess. Bands are made of aluminum and weigh 0.001 ounce, and were applied to the tiniest of bird legs using a regular pliers. As a weight comparison. It takes 50 bird bands to achieve the same weight of one grain of rice. Northern cardinals are the only bird tagged with titanium bands, as they tend to be aggressive and readily make short work of aluminum bands around their legs. Bands are imprinted with a unique identification number that any future finder of the bird can use to access the particular bird information on a national database.

Finally, birds were weighed. This was done by placing birds head-down in a tiny paper cone that was attached to a scale. This was the only step of the procedure that seemed to cause the bird a bit of distress. At no other point in the banding process did we observe any bird panic or flail. Each banding process took about two minutes.

On this particular day, we banded about 15 birds over the course of about two hours. Our catch included eight species of different birds. Our personal favorites were the golden-crowned kinglet and the ruby-crowned kinglet.

We banded a male common yellowthroat, known for its black Zorro mask.

We banded a Carolina wren who, despite its diminutive size, has a call louder than my guttural scream.

We banded a white-throated sparrow, which probably just arrived for a winter-over at the nature center property from the far northern reaches of Canada.

I asked the bird banders if the procedure hurts or disturbs the birds? They compared it to going to a doctor’s office - not really fun, maybe a bit unpleasant, but done for productive and positive reasons.

The banding process is often costly and labor-intensive, so what are the derived benefits? It aids ornithologists in getting a better grasp of bird dispersal and migration, social structure, certain aspects of behaviors, life-span, reproductive success, and population growth. In our case, a number of the birds that we banded were resident species (they live in the area year-round) while others were migratory, which means they are likely just passing through our area en route from their breeding grounds to the warmer wintering grounds to the south. Maybe some of these migratory birds will be caught by banders at the other end of their migration and much data and information can be drawn concerning its movements.

Learning more about bird migration is a major reason for banding. The concept of bird migration warrants a separate column, but it should be noted that scientists still are unsure how birds are able to perform their seasonal migration with such precision and timeliness. They often return to the same trees at the same time of year each year. Are they following stars (the actual migration usually happens at night)? Are they following an electromagnetic field that we cannot perceive? Are they just learning the route from previous generations of bird migrators and have a keen memory? So little is known at this point, but the continued banding of birds will hopefully keep providing peeks into this unique and mysterious behavioral trait.

* Mike Strzelecki is a freelance travel and outdoor writer, and 1981 graduate of Boyertown Area Senior High School. He writes from his house in Baltimore, Maryland. In his spare time, he joins his wife on adventures around the country observing and photographing birds.