Image

by Craig Bennett

(“A man cannot have a real appreciation of history until he’s old enough to have a little history of his own.” José Ortega y Gasset)

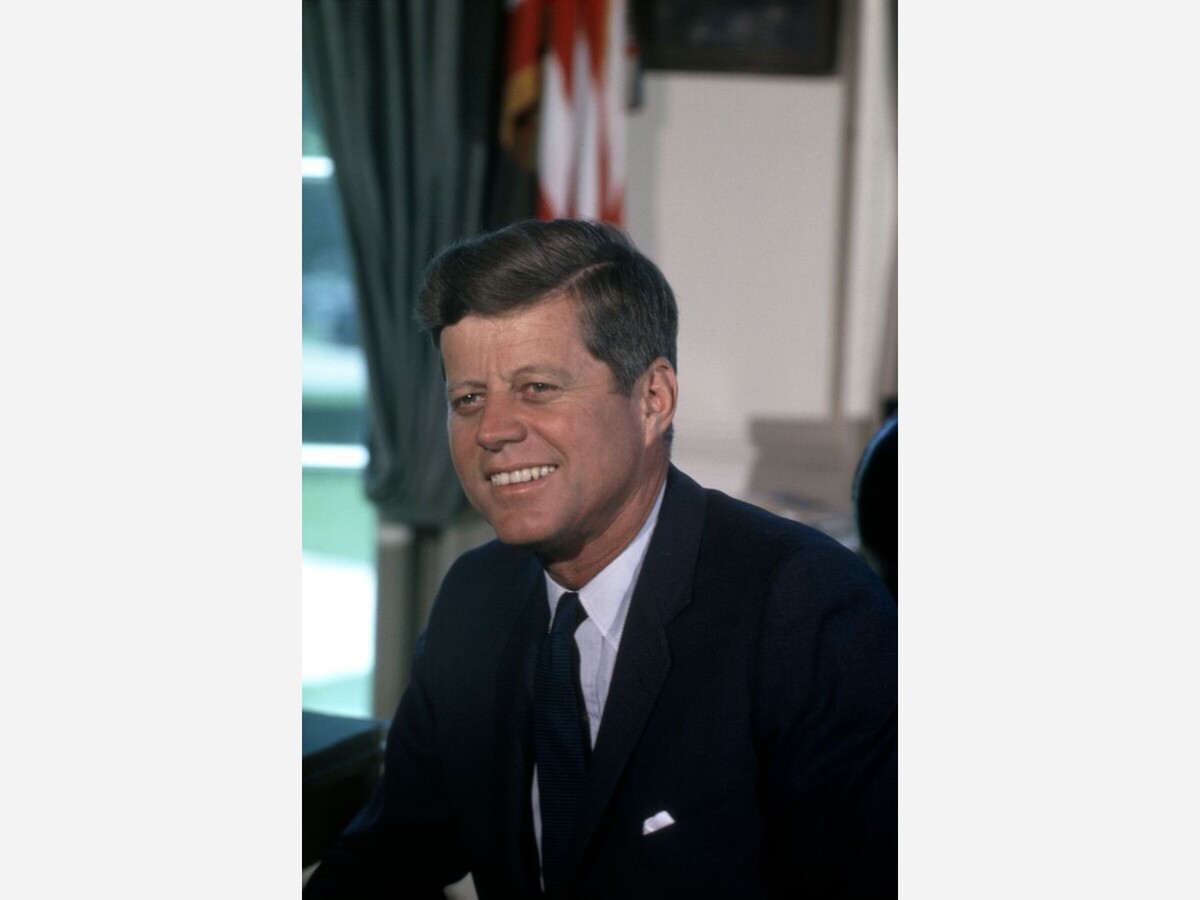

November 22, 2023, will mark sixty years since the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. There are precious few among us Boomers who cannot vividly recall those events as they were broadcast continuously over the radio and shown to us live over network television throughout the remainder of that traumatic Friday and the long week-end that followed. And though, in the decades since, we’ve witnessed many other incidents whose eventual effect on the world may far surpass that of the assassination of a U.S. president, we remember the Kennedy assassination with particular vividness. Perhaps this is because it was our generation’s first meaningful experience of bearing witness to history.

I was a sophomore in college that year, commuting to nearby Ursinus as a day student. On the afternoon in question, I had no classes scheduled and was home catching up on my studying when the telephone rang. It was my mother, who worked as a cashier in a small neighborhood grocery store just around the block from our house. “Turn on the radio,” she said, her voice tight with anxiety. “Somebody shot the president.”

My first reaction, of course, was disbelief. “She’s got to be kidding,” I thought to myself. “This is America. This is 1963. They don’t shoot presidents in America in 1963.” But I hung up the telephone and turned on the radio. Sure enough, someone had shot the president.

But the impression made by that initial shock was superseded by related events about to unfold in my own life. The next day I was with some friends from the neighborhood at the home of a fellow Ursinus student who lived just up the street. The topic of conversation, of course, was inevitable. When it was mentioned that the president’s body was to lie in state in the Capitol rotunda the following day, our host said, “Hey! Washington’s not that far away. You want to go?” We all looked at each other and realized that he was right and that such a thing was indeed possible. We nodded our heads in agreement and quickly laid plans for the trip.

The drive to D.C. was unusually quiet. Each of us was undoubtedly preoccupied with his own thoughts, pondering over and over the enormity of what had set us on this journey and what, if anything, it might mean to our immediate future. Once we reached the heart of the city, we found a place to park the car and joined the long line of people making their way ever so slowly toward the Capitol in the chilly darkness of that late November evening. It was just about eight p.m.

It turned out to be a long night. The line, which appeared to be of no great length from our initial perspective, actually snaked back and forth around block after block, which made it several times longer than it had first appeared. The hours passed slowly as we shuffled forward a few feet and then waited, time after time, enveloped in the frigid silence that lay like a pall over the thousands of people who waited along with us. It was growing light by the time we could see those ahead of us actually ascending the steps to the rotunda, and finally we found ourselves at its entrance. It was 7:30 a.m. It had taken us eleven-and-a-half hours to reach the Capitol.

Inside, the line was moving rather briskly around the bier. The black coffin, flag draped, was cordoned off by thick velvet ropes; and a military honor guard stood reverently at parade rest, their heads bowed. We followed the crowd around the interior of the rotunda, past the coffin, and out onto the steps at the east side of the building. The sun was just coming up over the shallow skyline of the city. The sky was clear, the air was cold and bracing, and somehow I felt…elated.

For the first couple of hours during the drive home, I wrestled with this bizarre contradiction. I had just spent a long, cold night waiting among thousands of other people to catch a quick glimpse of a closed coffin containing the body of a handsome, popular, dynamic young president who had been cut down in the prime of life, leaving behind a grieving widow and two little children. Why was I feeling so up? What was there about all of this that would justify anything but the deepest and most sincere feelings of compassion, shared grief, and perhaps an uneasy apprehension over the possible consequences to the country at large?

But eventually I realized why I felt that way. The occasion was tragic, no doubt about it. But this was also something about which people would be writing books, filming documentaries, and making speeches for decades to come. Memorials would be erected, commemorative events would be held, and school kids all over the nation would be learning about this long after I myself was in my grave. This was big. This was honest-to-God history—the real McCoy. And for the first time in my life, I had borne witness. However insignificantly, I had taken part. I had actually been present in the world when it happened and old enough to understand the staggering import of what had occurred.

When I was still very young, I became aware of the importance of World War Two to my parents’ generation and how they would sometimes ask each other, when the conversation turned reminiscent, “Where were you when Pearl Harbor was bombed? What were you doing? How did you hear the news? What did you do then?” Even though they had lived to see much that far exceeded that brutal attack in death and destruction, that was still the defining event of their generation. That was the initial encounter of their young lives with history of the first magnitude. And, as I grew toward adulthood, I would sometimes wonder what the defining event of my own generation would be. When my peers and I were as old as my parents were then, what would be the incident about which we would ask each other, “Where were you when such-and-such a thing happened? What were you doing? How did you hear the news? What did you do then?” On November 22, 1963, I had my answer.

And after I married and became a father, I would sometimes wonder what the defining event of my daughter’s generation would be. When they were looking back on their lives from the perspective of middle age and beyond, what common experience would they all remember vividly enough to ask each other those same questions. I hoped sincerely that it would be something positive—something good rather than tragic, beneficial rather than destructive. And then one bright, sunny morning in early September of 2001, I had my answer.

Now that we Boomers are older still, I’m sure that we wonder from time to time what the defining event of our grandchildren’s generation will be. When they are as old as we are now and look back over both their own lives and the life of the world in which they’ve lived, what event will prompt them to ask each other, “Where were you…? What were you doing…? How did you hear…?” Let us hope that this time it will indeed be something positive—something that will herald an era of peace, reconciliation, and general harmony among the peoples of the Earth. For otherwise, one day there may well be no more history—or anyone left to remember it.

-Craig H. Bennett, author of Nights on the Mountain and More Things in Heaven and Earth, available from amazon.com, barnesandnoble.com, and the Firefly bookstore, Kutztown,

PA