Image

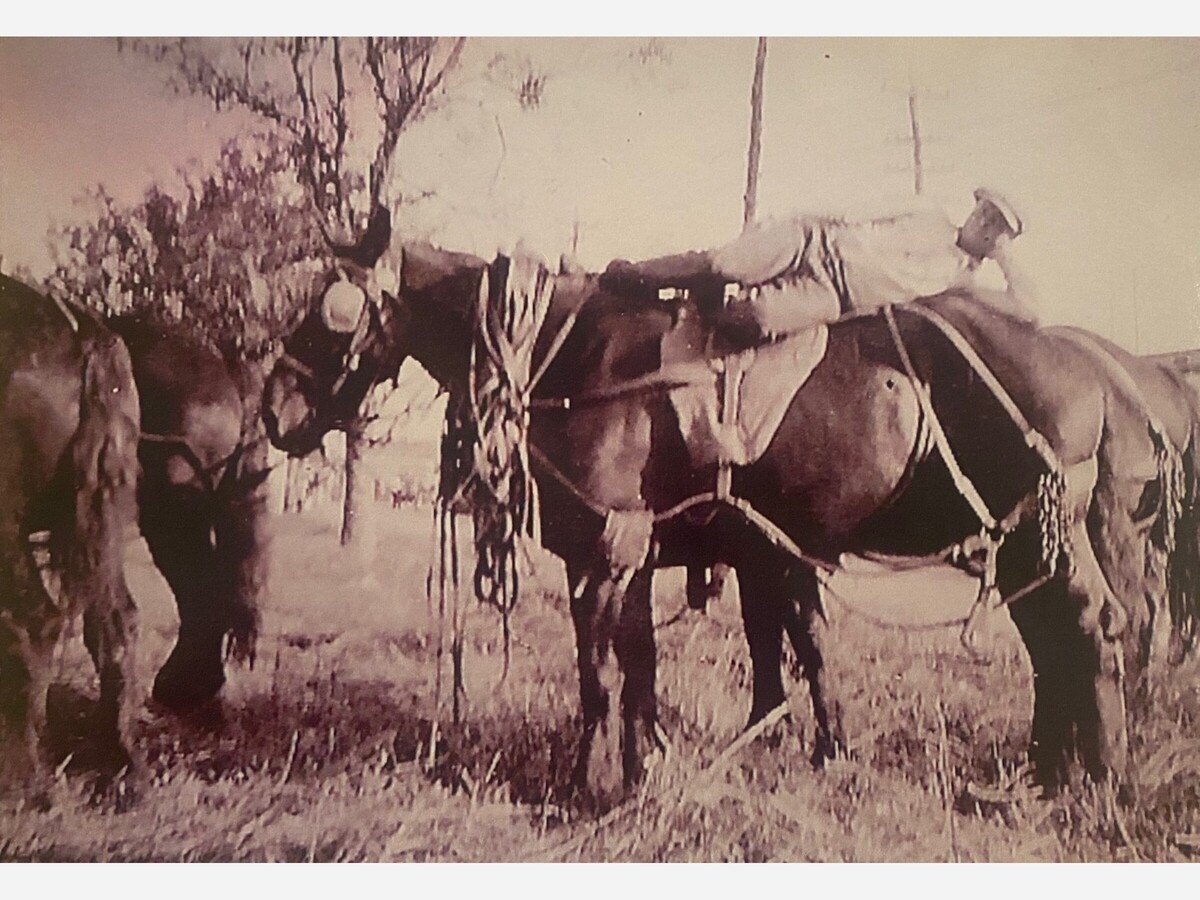

Photograph: Frank B. Updegrove, circus driver, only 5'6" easily poses on a black percheron wheel horse.

by Bob Wood

Two generations of students who attended Boyertown High School may recall retired geography teacher Bruce Updegrove. Updegrove’s students may have met him again in his role as adjunct professor of history at Montgomery County Community College. But the subject of this column is Updegrove’s father, Frank B. Updegrove, who was a driver of an eight-horse team for Ringling Brothers Circus from 1924 to 1928.

Frank Updegrove was born in 1903 and raised just west of Boyertown in Gabelsville. In 1923, when he was 20 years old, Updegrove scraped together $100, boarded a train in Boyertown, and headed for California to visit his brother Thomas--- “Texas Tommy”--- who had a wild-west vaudeville type show.

There followed a variety of jobs and adventures out West: sheep herding, copper mining and what not. He bought a colt six-shooter and a 1918 Buick for $20 each. He traveled with an outlaw (murderer) to Nevada where the outlaw asked to borrow the revolver. That was the last he saw of either of them. The car he lost playing black jack.

At the end of the year he returned home to Gabelsville and worked for Raymond Bahr in his saw mill. Bahr took Frank Updegrove to Reading to see a circus and that started a life-long interest. Boyertown tinsmith “Jakie” Stauffer, who had once been in the circus, still had a contact there, so Updegrove wrote to the man and told him he could drive horses.

He was offered a job and told to report to Bridgeport, Connecticut, where he was assigned as a helper to expert wagon driver Richard Sells. Of course, Updegrove could drive two-horse farm wagons, but the circus baggage and show wagons were vastly different. Driving an eight-horse team required considerable skill to keep the reins organized and the horses under control.

Stretched out while pulling, an eight-horse team alone was 70 feet long. Updegrove learned fast and was noticed by the boss hostler, Tom Lynch, who offered him a job as a wagon driver, and so his circus career was launched.

Updegrove visited all 48 states with Ringling Brothers Circus. He was the youngest eight-horse team driver at Ringling Brothers and was the envy of drivers who had been at it a lot longer. In 1925 Ringling Brothers traveled with 500 horses both baggage (working) and show (performing). Four trains of twenty-five cars each carried the show and usually traveled at night. By dawn they were at the next venue. That year the circus traveled 14,413 miles and set up the show 117 times.

The circus comes to town.

Rolling the wagons on and off the flat cars with a team of horses was an art. Updegrove loved his horses and cleaned and curried them every morning. The circus used gray percherons almost exclusively for their baggage stock. This strong, gentle breed traveled well and adapted to circus life.

At first light the drivers (They weren’t called “teamsters.”) would harness their team and head for breakfast. The circuses fed their help extremely well: nothing but the best. Updegrove had a habit of taking 8 pancakes with him from the breakfast tent each morning and feeding one to each horse. He had to start at the front of the team and work back. If he started at the back the front horses would turn around, anxious for the treat, and tangle the harnesses.

Updegrove was only 5 feet 6 inches tall and could not see over a percheron at the shoulder, so harnessing them was a task. After breakfast the drivers would pull the baggage wagons to the lot and an army of hands would erect the side shows, the menagerie, the main tent, seats and so on. The whole industry was made possible by a labor force that received very low pay. The main incentive for the help was the excellent food.

Like a general on the battlefield, the boss hostler would direct the set up from horseback. Since the circuses were erected in fields and lots well off street, soft sand and mud were the villains as they would mire the great loaded wagons which could weigh as much as 10 tons. Mud or not, the show had to be set up on time and sometimes as many as five eight-horse teams were “hook-roped” to one wagon to pull it through the mire.

Updegrove’s wagon carried the canvas for the horse tent where the horses were sheltered during the day while waiting to reload the train. By 11:00 a.m. they were set for the first of two shows. Each show ran for about 2 hours. Usually the circus only stayed in town for one day.

During the ’20’s Ringling Brothers seated about 10,000 patrons at each show. General admission was $1.00 and reserved seating was 50 cents more. But then, as now, the real money was in the concessions: sodas, ice cream, popcorn, balloons and such things as people liked to buy.

By late afternoon they were tearing the circus down, loading the trains and at nightfall pulling out for the next town. The hands slept on the train. Sometimes in the hot summer months they would sleep on top of the rail cars in the cool breeze. In the pitch-black night they had to be careful to remain lying flat as an unseen bridge would scrape them off the car; or, more commonly on hot nights, they slept on the flat cars under the wagons. When they woke up they were in the next town. Preceding them was an advance team that handled advertising and provisioning. The circus consumed vast amounts of hay, grain, feed and food.

Frank Updegrove only went to the 4th grade and didn’t write too well, but he wanted to keep a diary. Instead of writing, every day he took a photograph. Bruce has many of these photos and they are remarkable because they are pictures of baggage horses and the working side of circuses that were not commonly recorded. Most people took pictures of the show itself. Additionally, Bruce helped his father tape record a narrative of his many adventures from which much of the information for this article is derived.

Once in 1927 during a violent thunderstorm, Updegrove and another driver were driving a heavy wagon with two eight-horse teams hitched to it down a dirt road that the rain had made a “slippery, muddy mess.” The thunder and lightening panicked the horses, and they bolted down the narrow road lined with automobiles of circus fans. Despite all efforts to brake and hold back the reins, the wagon fish-tailed and badly damaged ten autos. The wheel horse’s hoof was crushed and it had to be destroyed. Certain they would be fired, the other driver walked away and was never seen again. However, Tom Lynch, the boss hostler, said, “Forget it, Frank. No man can hold back one run-away horse let alone eight!” Ringling Brothers paid for everything and Updegrove never heard another word about it.

Finally, one time in Texas, the circus was quarantined for two weeks by an outbreak of hoof and mouth disease and prevented from crossing the state line. Finally they got permission to leave, but on the way an elephant died of natural causes. They knew if they arrived at the check point with a dead animal, they would be turned back; so they stopped the train in the middle of the Texas desert. The men got off with shovels, dug a huge pit, buried the unfortunate pachyderm, and the train went on its way. Updegrove chuckled, “Some day when an archeologist digs there in the desert and discovers the bones of an Indian elephant, he will scratch his head and wonder just how it got there!”