Image

photo from The Library of Congress

by Bob Wood

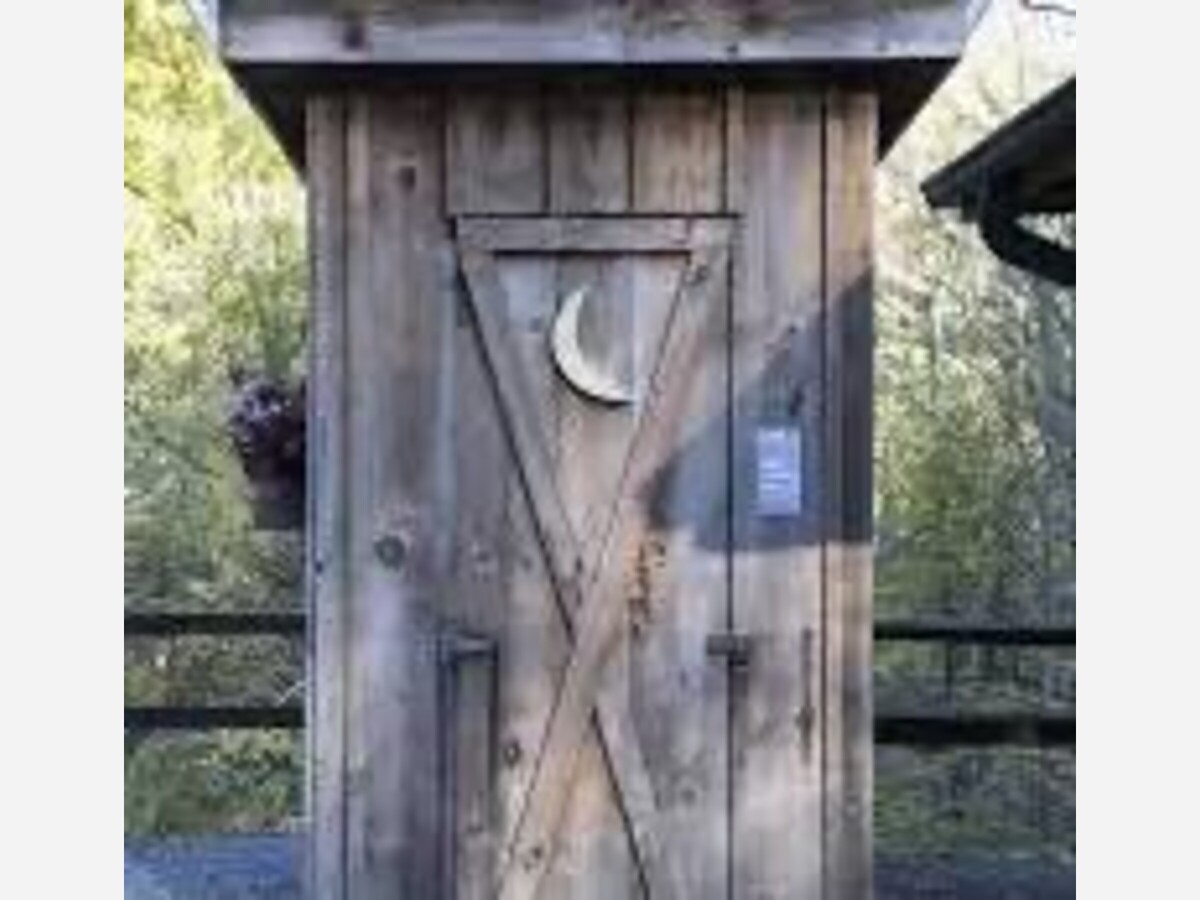

Most buildings of the Pennsylvania Dutch farmsteads were somewhat similar; bank barns, farm houses, spring house and such were more the same than they were different. However, although the shape of outhouses followed a familiar pattern, sometimes the construction materials and whimsical architectural flourishes gave the outhouses individuality not found in the other buildings.

Amos Long in his book “The Pennsylvania German Family Farm” pictures outhouses made with decorated lap siding painted in Cape May colors, louvered turrets, stained glass windows, beautiful brown sandstone work that would do any mason proud, slate roofs, fancy finials or even bird houses on the top. But outhouses on most farms were of humble materials: old boards nailed vertically with cracks that let snow cover the whole interior and leaking wood shingle roofs hastily covered with tar paper.

Known as the toilet, the one holer, the two holer, the white house, the back house, the little house, or some more earthy name, by the twentieth century the privy was found on every farm. Interestingly, there is no Pennsylvania Dutch word for the outhouse, so the Dutchmen adopted the English word “Privy” which became in Dutch “ ‘s Briwwi”.

Perhaps there is no Dutch word for Privy because it was a late addition to the farmstead. Research indicates that on local farms, outhouses appeared during the Victorian Era, usually post Civil War (1861-1865). Also, outhouses were usually built as a convenience for women and children; men ordinarily didn’t use them. Where then, one might wonder, did the inhabitants of the farms “answer the call of nature” if they had no outhouses?

In Vol. 3, pg. 702 of Henry Melchior Muhlenberg’s Journals there appears the following entry: “February 28 1786. Toward evening I went into the garden to perform an act of nature when I was overtaken by dizziness and fell into the snow among the currant bushes. I tried with all my remaining strength to get up on my feet or on my knees [Rev. Muhlenberg was by this time a very elderly man] but in spite of all my efforts I was unable to accomplish anything. Accordingly I cried out for help until my nearest neighbor heard me and came to my assistance.”

Rev. Muhlenberg, then living in Trappe, was perhaps our most sophisticated resident. If he had no outhouse, probably no else one did. Of course, there were the famous “privy pits” where modern day archeologists find broken china and other oddments being disposed of. But these are of a different area and a more urban culture. I speak here, instead, of the local Germanic farmers.

People defecated in the garden, in the barn, or behind the barn. Night soil from a chamber pot was emptied onto the barnyard manure pile. One woman had a place behind the barn where a corner in a rail fence allowed a rail to be placed catty-corner upon which she sat. Of course, boys, the story goes, cleverly sawed the rail part way through from the bottom so that it cracked when she sat on it.

These were earthy people of earthy habit. One reliable local researcher tells of an old Dutch woman in Upper Hanover Township, who about 1950, on a Sunday afternoon, with company, while showing her garden, squatted down and relieved herself. No outhouse needed .

As with most other things, outhouse construction was governed by the almanac. Custom held that the structure had to be built in one day while the horns of the moon were down and the moon was in the sign of the crab. This would assure that the deposited material would decay and dissipate into the earth lessening clean out.

Most outhouses in our area were not built over pits, or if they were, the pits were shallow. Some had small clean out doors in the back or side. Cleaning out varied. Some cleaned out the accumulation weekly and some hardly at all. One source said that in the early days when one-horse manure sleds were still used to take barnyard manure to the fields, some cow manure would first be put on the sled so that the outhouse contents did not touch the sled. Another reference said that first a layer of straw was placed in the bottom of the manure spreader so the outhouse contents did not touch the spreader: excreta from the outhouse being considered more foul than animal manure.

Recently, pieced patchwork and even quilted, small “privy bags” have appeared in tourist shops. Supposedly these small flat bags hung in outhouses and held the toilet paper of the day. I doubt it. For one thing, there were few if any privies used by the Pennsylvania Dutch during the period these bags supposedly derived from. Perhaps so called “privy bags” are actually “wall-pockets” that occasionally were hanging in some early kitchens as a keeping place for the newspaper or documents. Sometimes, though, there were rag-bags in the outhouses where old textiles were accumulated awaiting the rag and bone man, but the “privy bags” story needs some primary source citations before it can be accorded any substance.

Finally, as to the oft noted use for corn-cobs in this department…it’s true.

*An inspiring Jack of all trades, master of many, Bob Wood serves as Studio B's Gallery Adjunct when he's not busy doing everything else! Writer, artist, potter, historian, and volunteer. Bob began his career as an artist following his retirement from teaching Language Arts. Bob is a popular speaker; local history is his niche. Bob has published four books on local history.