Image

by Allison Kelly*

Imagine, if you will, the opening scene of a movie. It’s a beautiful spring day. The sun is shining, a gentle breeze is stirring the fresh green leaves on the trees, the flowers are blooming, and the birds are singing.

An exuberant trill rings out.

The sky darkens and a sudden gust of wind sweeps through the trees and sends cascades of flower petals to the ground. Birdsong ceases.

Another wild warble pierces the silence.

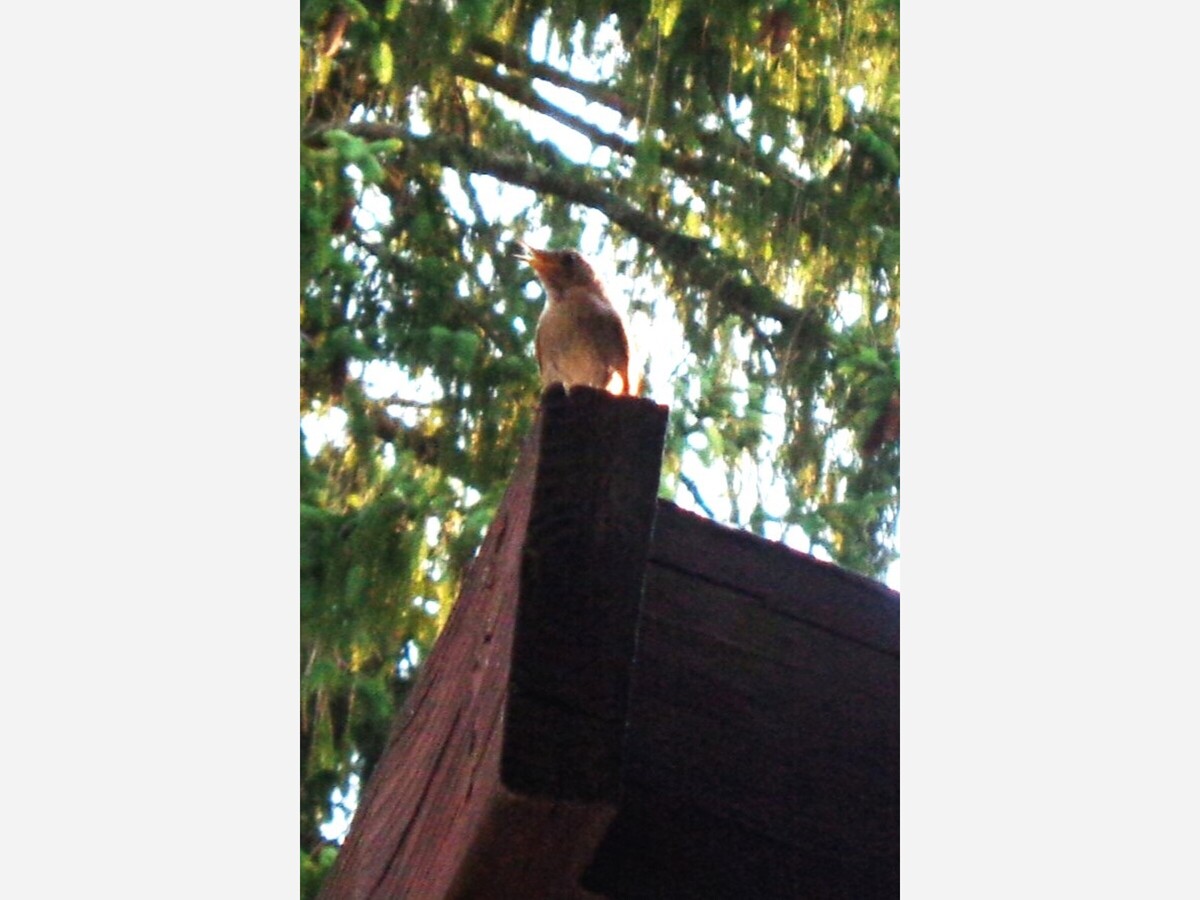

The ominous theme music from Jaws begins to play under the action, and the camera pans wildly from side to side, up and down, as if seeking the source of the melody. As the undercurrent of notes steadily builds in intensity and volume, the camera zooms in on a tiny brown bird perched on a blossom-laden branch of a rhododendron bush. The bird’s whole body shakes as it repeats its full-throated announcement: the House Wrens are back in town!

I didn’t use this scary imagery to convey the idea that wrens are dangerous (I have never seen the movie The Birds and do not intend to); I am trying to illustrate how I imagine the other birds feel about the dramatic entrance of the wrens each Spring. Like the shark in Jaws, their appearance disrupts a peaceful scene.

The House Wren is my favorite bird. It has many traits that I admire: confidence, bravery, persistence, a good work ethic, and excellent parenting skills. Not flashy like a cardinal, blue jay, or goldfinch, this nondescript brown bird is still number one on my list of birds to photograph. The fact that it is a challenge to capture a good shot of this bird makes any picture a success, so please excuse the quality of the photographs included in this article. As I’ve mentioned before, my severe rheumatoid arthritis makes it impossible for me to use a fancy camera with a big zoom lens. But even if you have high-tech equipment, I think the best way to get a good picture of a wren is to be patient and observe the bird’s routine so you know where and when to take your shot.

With that big voice, the house wren should be easy to locate for pictures, right? No. Its chaotic cascade of notes seems to come out of nowhere and echo from everywhere. It helps if you know where to look. The first step of the mating ritual is to choose a location for the nest. The male picks up sticks, stuffs them into every nook and cranny in a certain area, then presents the prospective homes to his mate. The female chooses her favorite and that is where the eggs are laid.

The persistence and work ethic of this small but sturdy bird is on full display when you see it trying to fit big twigs into a tiny opening of a birdhouse; the poor wren has trouble positioning the stick to fit through the hole but never gives up. It sometimes whistles while it works but is usually silent while focusing on the important task at hand. The house wren seems to have a never-ending supply of energy; it makes me tired just watching it gather sticks for a nest.

We have a nice birdhouse in our front yard (in view from one of our windows) that is visited every Spring by the bluebirds and wrens – they have even waged battles over it, the rhododendron bush shaking as the birds chase each other away from the beautiful house – but it is rarely used to raise a family. In 2021 I felt sorry for the bluebirds who had settled into the house in April, only to have the wrens arrive in May and kick them out! The fact that the wrens soon afterwards chose a different house in our birch tree made the whole situation more distressing.

I never saw any baby bluebirds, but I have seen wren offspring over the years. My goal is to get a photo of a baby bird leaving the nest for the first time (fledging). Since we have 10 birdhouses on our property – most of them in places where I can park my power chair at a respectable distance – I believe my best chance of achieving this goal is to keep a close eye on the birdhouse in use. I took the head rest off my power chair last year so I can lean back in my seat for a better view; otherwise, my fused neck makes it very difficult to look up into the tree.

Activity picks up around the birdhouse after the eggs hatch. Look for movement among the tree leaves. If you see the wren, don’t take your eyes off it. It can and will be quiet, especially if it is searching for insects to feed hungry babies. When the bird swoops down to the ground, it’s probably on the hunt; you should have a decent chance of getting a photo of it returning to the birdhouse with a bug in its beak. It might emit an angry chitter as it approaches; I think that’s a warning but could also just be the sound that comes out when its mouth is full.

The first time I saw an adult wren taking food to its babies I didn’t realize I’d captured the moment with the camera until I uploaded the photos to my desktop computer and enlarged them. I was fascinated to see the tiny worms and grubs the wren was feeding its young. I feel relieved when I see wren parents taking food into the house and flying out with white poop in their beaks; that means the little ones are alive and growing. If you have problems figuring out when it’s feeding time, stay near the tree and listen carefully; you’ll hear a faint but frantic chorus of baby wrens when their parents are approaching the house with a meal.

Last year I came very close to achieving my goal of seeing a baby bird fledge. On July 2, 2024, I got a shot of a little wren half out of the birdhouse’s opening. I swear I could see the determination on its tiny face. The next day the house was quiet, its occupants having flown the coop.

I felt bereft. Almost every day for two months I had been hearing the wren’s song, background noise that struck a soothing chord within me. I wish these tiny birds could stay the whole year and provide me with a such a stirring soundtrack for my life. Other birds may find their bold ballads a bit annoying, but whether it’s the joyful jingle of a male wren presenting a potential nest to his mate, the angry chitter of an adult wren warning me to keep my distance from its nest, or the shrill trills of hatchlings demanding food, it’s all music to my ears.

* Despite living almost her entire life with severe juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, Allison has always enjoyed the outdoors. Growing up on a family Christmas tree farm – she could literally go over the river (creek) and through the woods to her grandmother’s house – instilled a love of nature in her at an early age. As an adult she uses a mobility scooter or power chair to get up close to nature and take photos that she turns into note cards available for sale at Engage Arts Studio, 1005 Gravel Pike, Schwenksville or The Collective, 10 S. Hanover Street, Pottstown. If you would like to read more about the birds in Allison’s back yard, purchase a “Feathered Friends” snail mail subscription from her online shop at www.noteworthynaturephotos.com.